We Can Teach Grammar Better Than This

By Sarah Tantillo

As we move into summer—or what I like to call “curriculum writing season”—we have an opportunity to reflect and improve upon the work we’ve done this year. Writing or revising curriculum enables us to strengthen instruction. To that end, I’d like to share a new resource that aims to solve a very common problem.

The problem is this: We need to teach grammar more effectively.

Grammar instruction to date has suffered as a result of several key factors. For one, many teachers did not receive effective grammar instruction themselves, so they are uncomfortable with teaching it. It seems outdated and old-fashioned, like riding a horse and buggy to go visit someone in the next town. After all, we have cars and phones! When elders talk about how they used to “diagram sentences,” it sounds dry, dull, and quaint. No one wants to go back to those olden times.

Uncertain of the rules and how to present them in an organized and purposeful way, some teachers barely touch on grammar or skip it altogether. Others rely heavily on textbooks that present rules in isolation with repeated drilling as the primary mode of instruction. Talk about “olden times”!

While students might be able to complete the drills, they often fail to apply the rules in their own writing. This reinforces the impression that teaching grammar seems pointless.

Also problematic is that many materials available to support grammar instruction are not helpful—or worse, they actually undermine students’ understanding of grammar, syntax, and writing. It feels like we’re headed for a “post-grammar world.” But we can change direction. The key is to have our students wrestle with grammar, not just try to memorize it.

How we frame grammar instruction matters.

If you view grammar as “fixing incorrect sentences,” you teach it that way. If you view it as “building strong, compelling sentences,” you take a different approach. My latest book, Using Grammar to Improve Writing: Recipes for Action, explains a new way to teach grammar—systematically and purposefully—in order to strengthen student writing. It offers detailed guidance on every single K-12 language standard, including which grammar standards to teach when and how to use grammatical forms to capture ideas. This new approach will enable students to write more efficiently and effectively.

During the last weeks of school this year, a group of teachers I was consulting with downloaded the eBook version onto their laptops (using the free Kindle app) as they drafted units so that they could instantly incorporate the guidance for key standards.

Here are two examples of that standards guidance, one from 4th grade and one from 8th:

L 4.1.E: Form and use prepositional phrases.

TEACHING THIS: [This repeats L K.1.E and L 1.1.I.]

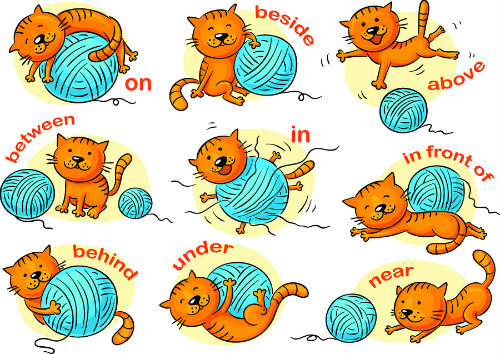

Prepositions should be taught in kindergarten and 1st grade, but they can continue to be tricky, especially for ESL/ELL students who struggle with idioms (e.g., “Is the ball IN the air, or ON the air?”). [1]

Prepositional phrases are simply prepositions followed by a noun (on the chair) or a noun equivalent (by working hard). In case you need to review this standard with students, here’s that guidance:

► You will need a soft object such as a squoosh ball or a small pillow—something that won’t hurt anyone. Place the object in various locations and emphasize the phrases that capture its location: “The ball is ON the desk. The ball is IN the closet. I brought this ball TO school today FOR you.” Invite students to generate their own sentences emphasizing the prepositional phrases.

► As always, reinforce oral language with visual support such as an anchor chart listing the prepositions you want them to use or a PowerPoint presentation that quizzes them.

ASSESSING THIS:

First, read aloud sentences and invite students to identify the prepositional phrases (e.g., “to him”). You can engage the entire class in practice by doing this with a rapid-fire turn-and-talk approach. Don’t forget to model this: “I’ll say the sentence once, then Partner A will turn to Partner B and restate only the prepositional phrase to Partner B. For example, if I said, ‘I gave the book to Joe,’ Partner A would turn to Partner B and say, ‘TO JOE.’ Let’s see a model pair try this….” Select a pair to demonstrate, then launch a whole-class attempt. Then cold-call and clarify if anyone was confused. Run a few rounds, then switch the partner roles.

► Students should move from identifying the phrases to imitating your sentences using prepositions, then writing their own.

► Cloze reading (text with blanks where, in this case, the prepositions belong) is another useful way to check for understanding.

L 8.1.B: Form and use verbs in the active and passive voice.

TEACHING THIS:

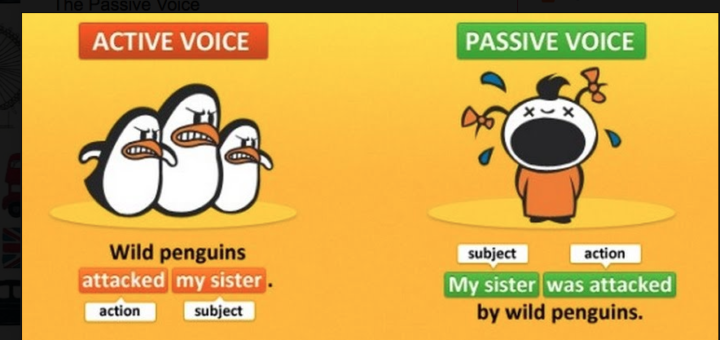

This is a fun one! As most experts will tell you, it’s preferable to use the active voice in order to show who/what is doing the action. [2] For example, “The teenagers spoke up about the need for gun control” sounds more coherent and less clumsy than, “The need for gun control was spoken up about by the teenagers.” That said, sometimes it is more appropriate to use the passive, such as when you want to emphasize the receiver of the action or to minimize the importance of the actor, as follows:

► “The students and teachers were forced to seek shelter when the gunman opened fire” emphasizes the victims.

► “Lemons and oranges are grown in warm climates” minimizes the importance of the actor (We don’t need to know the names of the farmers).

► Also, some academic/scientific writing requires the use of the passive voice (because we don’t need to know who collected the data, or we already know, and a lab report is not a memoir).

► Show students two sentences: one in the active voice, the other rewritten awkwardly in the passive (as in the first example above). Ask them which is preferable, and why.

Pitch: Even though both sentences say the same thing, that second example sounds very clumsy. That’s because it’s in the passive voice, as opposed to the active voice we see in the first sentence. Today we’re going to explore when and how to use the active or passive voice so that you can be sure your writing emphasizes what you want to emphasize and is as clear as possible.

► Show them some more pairs of contrasting sentences to evaluate. Then give them some sentences written in the passive to convert to active, and vice versa.

Pitch continues: OK, so now we have the hang of the difference between active and passive voice, and we can see how awkward the passive can be. Now let’s look at some examples of APPROPRIATE use of the passive. Because sometimes the passive is preferable. Let’s see if we can figure out some rules for when it’s better to use the passive.

► Show students the second set of examples from above (or your own imitations) with a few more that mimic them, and let them try to figure out (1) what is being emphasized or minimized and (2) why the passive is preferable in such a situation. Students should write their own sentences mimicking the appropriate usage of the passive voice.

ASSESSING THIS:

As always, we want students to demonstrate their grasp of these grammatical concepts in their own writing, first in sentences then in paragraphs.

► Give them lots of practice in imitating sentences that use the forms. Then have them include several of the passive and active verb forms (underlined and labeled to show they know they’re using them) in a paragraph about a text or topic they are studying. Tell them you will score the paragraph based on two things: (1) All sentences must be complete, and (2) They must use the passive and active forms correctly and appropriately.

► For a quick diagnostic, give students two paragraphs: one in which all of the sentences are written in the passive voice, the other in the active. They should rewrite the paragraphs in the opposite voice. For a follow-up question, they should identify any sentences that would be more appropriately left in the passive and explain why.

Learning grammar patterns for clearer writing

What I hope you noticed about the guidance above is that we do not begin by requiring students to copy down the definitions of grammar terms, which is a common but demotivating approach. Instead, we invite students to wrestle with grammar patterns and, like detectives, figure out how grammatical forms work. Then they can use these forms in their own writing. Like magic. Though pitched as a grammar instructional manual, this is secretly a book about how to teach students how to write clearly. I hope you’ll check it out!

[1] For some helpful resources on teaching idioms, see the TLC “Idiom Power” page at https://www.literacycookbook.com/page.php?id=7.

[2] Diana Hacker and Nancy Sommers, Rules for Writers (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016, 8th edition), 126-127. My examples are derived from the explanations on these pages.

____________________________

Her other books include Literacy and the Common Core: Recipes for Action and The Literacy Cookbook: A Practical Guide to Effective Reading, Writing, Speaking, and Listening Instruction, both published by Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Sarah consults with schools on literacy instruction, curriculum development, data-driven instruction, and school culture building. She taught English and Humanities in both suburban and urban public schools, including the high-performing North Star Academy Charter School of Newark. For more information visit her website The Literacy Cookbook and her TLC Blog.

While there is merit to many of the strategies mentioned in this article, I take issue with the writer’s denigration of sentence diagramming. To be sure, sentence diagramming is not effective for all students, but it works well for visual learners.

To me. as a highly effective, veteran teacher of grammar, I value all strategies.

I recommend, consequently, that all grammar teachers use the strategies mentioned in this article; moreover, I further recommend that

All grammar teachers earn a minor in Latin.

All grammar teachers amass a plethora of strategies, including time honored strategies such as memorization of grammatical rules and sentence diagramming.

Hi, Richard– Thanks for reading my post and taking the time to write a detailed response. As someone who was taught sentence diagramming in middle school and Latin in high school, I share your passion for both. That said, as I noted, few teachers teach sentence diagramming any more; the pool of potential teachers who might has shrunk increasingly over time, and I don’t think we are going back there. I found your comment that it “works well for visual learners” of interest because I have read a lot of research on various approaches to grammar instruction and have not come across that finding; possibly you see it in your own classroom, but it has not been widely documented. Ultimately, I hope we are all on the same team in that we all want to help students write more effectively. And I agree with you that there is not one single correct way to make that happen. Thanks again for your enthusiasm for this work. Cheers, ST

Sarah,

I have taught high school English and Latin for nearly four decades. I can supply you with plenty of anecdotal evidence regarding the efficacy of sentence diagramming in regard to visual learners. I learned early in my career that no one strategy works for all students. With that in mind, I have routinely put a sentence diagram on the board for a particular issue–a long participial phrase interrupting the subject and verb, for example–in tandem with having students use different color pencils and crayons to code the parts of the sentence. I use many of the same strategies as you do. I have even had students perform grammar operas.

There are very few teachers left who know, for example, that the Objective Complement in English is a hold over from the Latin Accusative Infinitive or that the subject of a gerundive phrase must always be written in possessive case.

It does not surprise me that there is little published evidence regarding sentence diagramming and visual learners.

Very few teachers speak the language of grammar frequently; moreover, standards governing a teacher’s grammatical preparation fluctuate wildly.

Best of Luck with your text.

Hi Sarah,

This article is just brilliant. As a consultant and trainer of best practices, I am acutely aware of grammar’s role in true fluency in any language. The mistake many have made is to teach it very much in isolation. I am strengthening my focus to teach grammar explicitly, yet contextually and am always seeking new and effective ways to make grammar fun and meaningful for teachers and students alike. Your book looks to be an invaluable resource. Can’t wait to buy it!

Best,

Anne Swigard