Honing Our Questions to Deepen History Learning

How do we create more thoughtful, skillful learners of social studies?

This question was our district learning team’s focus as we began our work last year with middle school social studies teachers. It was a question that involved layers of thinking, planning, researching, collaborating, and experimenting among our team members to come up with some imperfect, yet possible answers.

We quickly discovered there will never be a single way to address this complex work, but focusing on the essential questions as the backbone of our instruction was a strong place to start.

Establishing a common understanding

When tackling the complex work of shifting instructional practice, it’s necessary to have all stakeholders share a common understanding of our goals. We had used essential questions for years – they were included in our curriculum maps and often posted in teacher’s classrooms. But were our essential questions REALLY essential questions?

We turned to Grant Wiggins to define and shape our understanding. Wiggins (2007) reminded us that a question is essential when it:

1. Causes genuine and relevant inquiry into the big ideas and core content.

2. Provokes deep thought, lively discussion, sustained inquiry, and new understanding as well as more questions.

3. Requires students to consider alternatives, weigh evidence, support their ideas, and justify their answers.

4. Stimulates vital, on-going rethinking of big ideas, assumptions, and prior lessons.

5. Sparks meaningful connections with prior learning and personal experiences.

6. Naturally recurs, creating opportunities for transfer to other situations and subjects.

Wiggins’ ideas can be a lot to unpack. Think of it this way: at the heart of the work, an essential question invites students to discover, think deeply, discuss, and shape their own understanding of the information.

An essential question is timeless – a learner can revisit these kinds of questions at different points in their life and share what they now believe or know in response to the question. For us, an essential question became the necessary anchor to our instruction and the starting place to establish clear student learning goals.

Our team* easily agreed true essential questions were necessary in all our social studies classrooms because they help establish a culture of thinking and discovery. We also agreed that our students deserve the opportunity to inquire, question, interpret and talk to grow their understanding of history from multiple perspectives.

Looking at our questions with fresh eyes

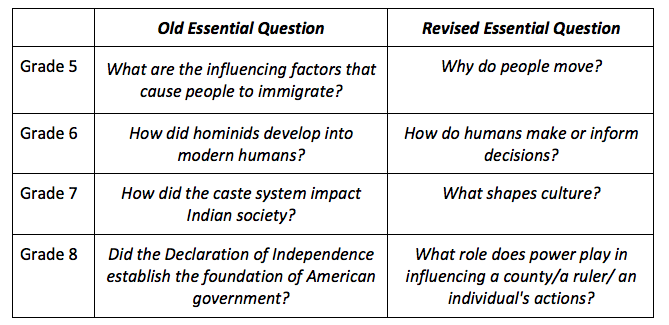

Once a common goal was established, we had to decide where to begin our work. Since we realized that not all the essential questions are created equal, we knew it was time to revise the ones we were currently working with in our curriculums.

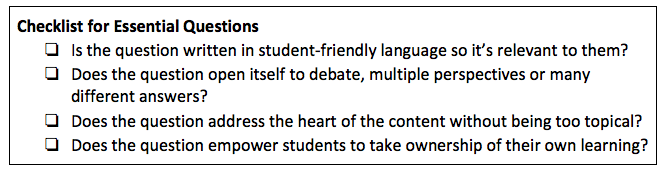

Using a checklist helped us assess our current essential questions and determine if we wanted to keep them, revise them, or discard them altogether.

After several attempts and many iterations, here’s a snapshot what we came up with:

Great…Now what?

Once we had two or three essential questions for every unit, we had to figure out how to implement these questions in the classroom. We turned once again to Wiggins – this time his 4 Phases for implementing an essential question. His process provided a necessary framework, demonstrating how the essential question could live and breathe inside a unit or units of study.

Phase 1: Introduce the question

In this phase we are getting students curious and building excitement. We are establishing a common understanding regarding the lingo of the question and providing initial opportunities for exploration and discovery.

Phase 2: Gather plausible, yet imperfect answers

Next, we see what understanding the students are already bringing to the question. Students use their current knowledge and some initial exposure from Phase 1 to respond to the question. Answers will be varied in depth and understanding due to the ambiguity of the question and the diversity of learners in the classroom.

Phase 3: Introduce and explore new perspectives

This phase is where the instructional heavy-lifting comes into play. The students engage in experiences in which they share text, resources, and phenomena which extend inquiry and/or question tentative conclusions reached up until this point. We elicit and compare new answers to previous answers, looking for possible connections and inconsistencies to probe.

Phase 4: Come to tentative closure

We wrap up the process by asking students to generalize their findings, new insights, and remaining questions about both content and process. We know at this point there isn’t a final answer to the question; the elasticity of the essential question means we can revisit them again on our learning journeys.

This process was crucial to our planning because it allowed teachers to see the scope of an essential question as it lives in a unit of study. We realized that process could extend across several units or be used side by side for multiple questions within a unit.

Using questions to assess understanding

As we began to use our essential questions in the classroom, we were not surprised when new questions arose. While we now had questions that fit the criteria of being essential, and we had a framework for how that essential question fits into a unit of study, we were left wondering: How can we use the essential question to assess our students? And what do the students’ responses tell us about what they’re ready for next?

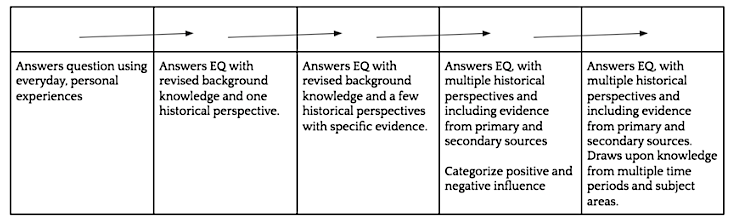

As curious learners ourselves, we researched, ultimately landing on Kate and Maggie Roberts’ work [DIY Literacy, 2016] with micro-progressions. Micro-progressions provide a model of a skill that increases in sophistication. Creating a micro-progression for the skill of responding to an essential question quickly became a treasure in our teaching toolboxes.

We now had a common understanding of what our end goal was and we could more effectively assess students and plan instruction to move them forward along the progression.

A process we found helpful when using a micro-progression:

►1. Sit side-by-side with a student and ask them the essential question as a pre-assessment. Listen carefully to their response. Be aware of how much you might be prompting a student since you want to get a true understanding of where they stand alongside the EQ. Think which step alongside the progression is the best match for that student at this point in the unit. Try to not think of this as a “score,” but rather a starting-off point.

►2. Once you get to talk with all the students, look for patterns. One possibility is to create small groups with students who fall in the same step. Oftentimes, students will benefit from the same instruction if they fall on the same step. This will help you effectively plan small groups to meet the needs of all your students.

►3. Next is to plan instruction. Think to yourself, “If a student is at step 2, what content and skills do I need to teach them to move them to step 3?” It’s important to remember we often don’t skip steps in a progression, so be intentional about what your students need at each step along the progression.

►4. Continue with inquiry and instruction, exposing students to new perspectives and multiple resources. Create opportunities for individual exploration and collaboration time so students can use their classmates to grow new understanding.

►5. Circle back to the students and ask them the essential question again, ideally multiple times throughout the unit. Notice (and celebrate) how they are growing alongside the progression. Provide feedback regarding what content knowledge and skills are in place and what the possible next steps could be to move up the progression.

Planning instruction using micro-progression

The final piece of our puzzle was using the essential question and micro-progression to plan instruction. Because it is hard to predict what the outcomes will be when using the micro-progression, we offer you a step-by-step that we follow with one example to illustrate these steps.

1. Note the step within the progression that matches the student:

We noticed that Micah had a grasp on some concepts taught in a previous unit. This is important and also creates a whole set of learning opportunities that we could design for her and others who had similar answers to the EQ.

2. Think, “What would be most helpful for this student to help her move from where she is to where she can grow?”

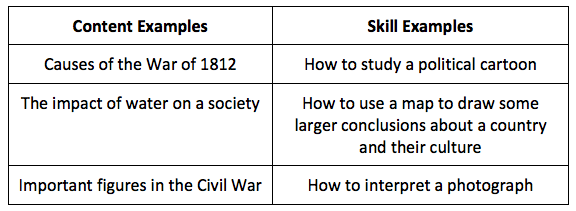

As we pondered the answer to this question, we decided that one of the gems of her answer was the recognition of the importance of water to a culture. Being that we were in a new study of Asia, we decided that the first step would be to take a look at a map of Asia and begin to make interpretations about the culture based on the map.

3. Gather resources:

We tried to keep this as simple as possible. Instead of an entire chapter of a textbook, a whole article, or even a documentary, we took a map of Asia and designed a list of questions that supported a deep look into this map.

4. Create a series of learning experiences:

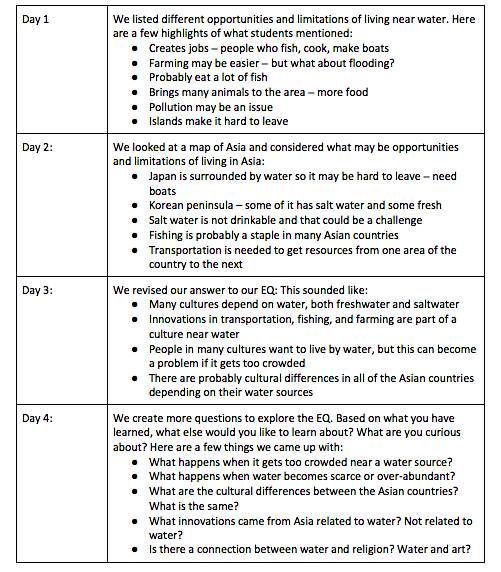

Micah was not alone in the type of answer she gave. We gathered others who could use the same experience and built a series of small group events that lasted about 10 minutes or so (yes, this can be done whole class; however not everyone in the class would benefit from this experience so we chose to do this in small groups). Here’s what it looked like:

Download here

Did all this work have a learning payoff? Yes!

You are probably seeing that some deep thinking came from students when we started with an essential question, took some time to analyze students’ “plausible yet imperfect answers,” and made instructional plans in response to these answers.

The immediate results were much more in-depth answers to EQ’s. The long-term impact was remarkable – students were much more curious, collaborative, and invested in social studies. Just what a teacher dreams of!

Resources:

► Essential Questions (2013) by Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins

► DIY Literacy: Teaching Tools for Differentiation, Rigor, and Independence (2016) by Kate and Maggie Roberts

*Our team consisted of the teachers, coaches, and administrators from Paramus (NJ) Public Schools with the guidance and leadership of our professional learning consultants from Gravity Goldberg, LLC (@drgravitygLLC)

Katie McGrath is a middle school instructional coach in the Paramus, New Jersey Public Schools. Prior to coaching, she taught middle school language arts for 12 years. Katie has written literacy curriculum for the middle school and she coaches in classrooms regularly. She has studied with Gravity Goldberg and her team of literacy consultants for many years and is a proud member of the Gravity Goldberg, LLC. Coaching Co-op. She is a current member of NCTE and the Lit Together Think Tank as well as a faculty leader at the Paramus Summer Literacy Institute. She can be found on Twitter @MrsKTMcGrath.