Bring Focus and Fun to Academic Vocabulary

A MiddleWeb Blog

What comes to mind when you hear the word ‘foil’? Do you think of a shiny roll of aluminum ‘foil’? A new form of surfing? Or perhaps a struggling person tied to railroad tracks by a villain whose plans are ‘foiled’ at the last minute by a heroic rescue? Or, does something completely different enter your brain?

Sometimes student learning can get lost in a muddled maze of academic vocabulary. As they move through the school day, our kiddos encounter hundreds of terms/concepts in a variety of contexts and content areas.

The word ‘foil,’ for example, has a completely different meaning in a math class where we work to multiply binomials than in English language arts where we are reading and analyzing a story. This specialized language can prove challenging and even problematic, particularly for our English Language Learners and students with special needs (Wilkinson, 2019).

Valuable Vocabulary

School is essentially “a world of words” where the language switches every time the subject matter changes. In addition, students’ reading needs and the demands of school curricula – particularly in heavily text-based, content-area classrooms – make it necessary for teachers to explore ways to identify, present, and reinforce crucial vocabulary (İlter, 2017).

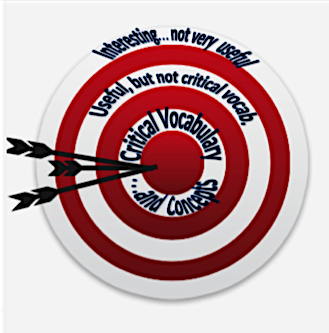

As we develop assessments and learning activities, one of the most important things we can do is sort and sift key terms into categories, such as…

- Critical vocabulary and concepts

- Useful but not critical vocabulary

- Interesting but not necessarily useful vocabulary

Teachers can then target the first category – critical terminology – in their classroom with multiple means of vocabulary instruction. Students, in turn, can focus their attention and effort on the most crucial elements of a lesson, rather than trying to guess what’s important.

Vocabulary Instruction that Sticks

By and large, research underscores the need for each of us to make time for instructional activities/strategies that bolster both students’ access and use of key terms (Townsend, 2015; Flanigan & Greenwood, 2007). This includes:

- Actively engaging students in word learning

- Immersing students in vocabulary repeatedly in a variety of contexts

- Helping students personalize vocabulary

- Guiding students in building connections/relationships between related terms

From Ms. T’s Got Class blog

As I wrote about in an earlier post, it’s helpful to first determine what students already know, as well as what misconceptions they have – in this case, about the vocabulary being taught.

One of the simplest ways to do this is by asking students to draw what they think of when they hear a particular term, using paper or dry erase boards. Of course, it’s okay if they haven’t heard the word before or they’re unsure what it means.

Tools like Padlet, Scannable, and CamScanner are pretty handy for quickly digitizing student drawings. Survey tools such as Google Forms, Poll Everywhere, and Typeform can also be used to assess students’ background knowledge and identify potential misconceptions.

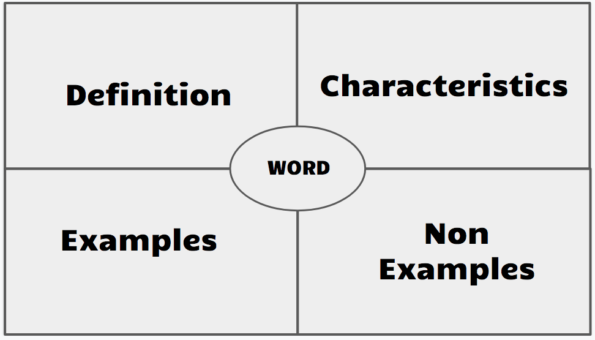

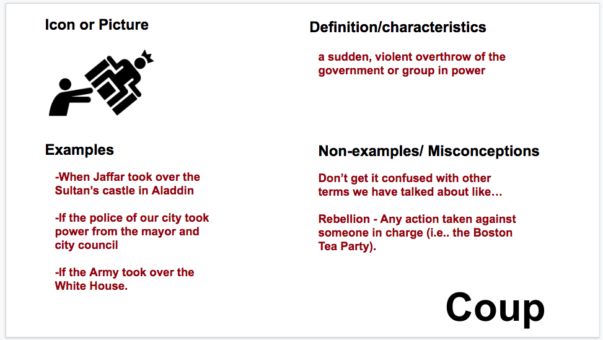

Teachers must also provide students with an explanation, descriptions, and/or example of the vocabulary term. When using slides as part of instruction, I like to use a template such as this one (shown below) to ensure that I am covering all the bases when presenting new terms.

When it comes to finding icons and images to clearly and simply illustrate a term or concept I utilize an icon plug-in for Google Slides or sites like the Noun Project, Pixabay, and Unsplash.

For vocabulary to stick, it’s important that we ask our students to reword and restate explanations and descriptions of terms in their own words. I like to have students visit in pairs and work to teach one another about the term, alloting about 30-45 seconds for each teammate. This gives me (and them) a chance to listen in and then identify/correct misunderstandings.

Teachers should seek to engage their classes in activities that encourage students to add to their knowledge of key terms (Marzano & Simms, 2011). One way for students to develop an understanding of and connections between terms is to provide a template for our kiddos to design/create their own study slides of important terms.

Here are a few Google Slides templates to choose from thanks to Alice Keeler and Debbie Campbell. Another idea is to ask students to create a vocabulary notebook of related terms (example 1 and example 2). Google Slides is an ideal tool for either activity because it automatically saves changes and allows students to work individually or collaboratively.

Word Game Time

Few things are more important than creating a playful, fun atmosphere around learning. Vocabulary games are a fantastic vehicle. They provide students multiple opportunities for word interaction, review, and repeated exposure to important terms (Kingsley & Grabner‐Hagen, 2018). Below are several options:

No-tech Options:

- Mini Vocabulary Games from Flocabulary

- Ten Classic Games for Vocabulary

- 9 Vocabulary Games from Magoosh

- Vocabulary Versions of Headbanz, Pop, Connect Four

Online Vocabulary Games

- Quizlet for students or teachers to create flashcards for study practice.

- Kahoot for gathering fun, fast feedback on what vocabulary terms students have mastered and which ones they struggle with.

- Flippity can easily turn a Google Spreadsheet into a Set of Online Flashcards and Other Fun Games.

- Study Stack allows students to Play Games from Flashcards They Create.

Bring Focus and Fun to Vocabulary Study

Our students want to be successful. Sometimes, however, they get a bit lost in the labyrinth of subject-centered vocabulary.

As teachers we can make the path a bit clearer by homing in on critical vocabulary, engaging students in repeated word play, helping them personalize vocabulary, and fostering lasting connections between concepts.

References

Townsend, D. (2015). Who’s Using the Language? Supporting Middle School Students with Content Area Academic Language. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(5), 376–387.

Flanigan, K., & Greenwood, S. C. (2007). Effective content vocabulary instruction in the middle: Matching students, purposes, words, and strategies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 51(3), 226-238.

İlter, İ. (2017). Concept-Teaching Practices in Social Studies Classrooms: Teacher Support for Enhancing the Development of Students’ Vocabulary. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 17(4), 1135-1164.

Kingsley, T. L., & Grabner‐Hagen, M. M. (2018). Vocabulary by gamification. The Reading Teacher, 71(5), 545-555.

Marzano, R. J., & Simms, J. A. (2011). Vocabulary for the common core.

Wilkinson, L. C. (2019). Learning language and mathematics: A perspective from Linguistics and Education. Linguistics and Education, 49, 86–95.

Thanks for sharing