Media Literacy: Video As Primary Source

Most of us have been closely attuned to video news sources over the last several months, as we’ve sat at home and followed developments in the Covid-19 pandemic in our towns and cities around the nation and across the globe.

The nearly 9-minute video of white Minneapolis policemen restraining George Floyd, who died at the scene, has sparked weeks of outrage, protest, and civil and government violence. Segments of that cellphone video have been seen countless times on television and internet news and in social media, and we can be certain it will serve as primary evidence in the ongoing criminal investigation and prosecution of Floyd’s death.

Ultimately, this and related professional and amateur video streams will also become “primary source material” for future historians – and for teachers of social studies and media literacy.

Moving Imagery and History

Exploring how film and video availability has evolved over the past century – and the impact that evolution has had on shaping the way history is written – can be the basis for meaningful media literacy lessons inside the social studies curriculum.

In this post, I’ll call attention to some high profile points along the historical continuum when the existence of film footage, video, or live television made history more vivid and memorable.

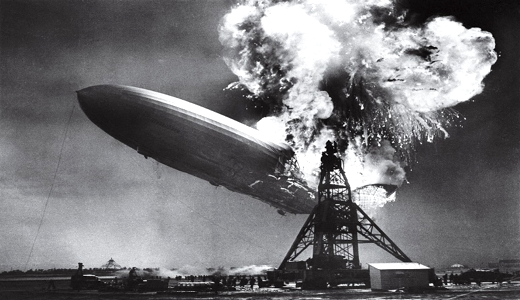

► The Hindenburg. Many of us have seen the dramatic film footage and voiceover when the Hindenburg airship exploded shortly before landing in New Jersey in 1937. Some may not realize that what they’ve seen is not live newsreel footage but a radio report that was “married” to motion film decades later – to powerful effect. The story is well-told in this article, “Oh the Humanity: Herbert Morrison and the Hindenburg”, where you can see both the original married video and a more complete version with radio reporter Morrison’s voice restored to normal speed.

► The Holocaust. Shortly after the end of World War II, the horrors of the Holocaust became widely visible as photographers and filmmakers recorded survivors being rescued by arriving troops. Many Americans first experienced this footage at movie theatres where they received news via the newsreels of the time. The Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum “is one of the world’s most comprehensive informational and archival resources for moving image materials pertaining to the Holocaust and World War II.” (See some curated film.)

Group of teen survivors at the Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz. (BBC News)

► The Civil Rights Era. Civil rights unrest in the late 1950s and 1960s was a regular story on the network nightly news broadcasts. The August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King Jr gave his famous “I Have A Dream” speech, came into American living rooms via TV. Throughout this period, films made by news crews and civilians documented the sometimes extreme violence of white mobs and police. The Newseum offers a video lesson built around a nine-minute documentary that includes many examples of primary-source news footage.

For more see “Television News and The Civil Rights Struggle” and “Media’s Role During The Civil Rights Movement” (video) and a timeline, Boycotts, Movements and Marches.

► The Challenger Disaster. When I was young, I was riveted to the TV screen every time astronauts blasted into space from Cape Canaveral. Those Gemini and Apollo missions were followed closely and carried LIVE on television as they happened. On July 20, 1969, many millions watched the grainy black-and-white image on TV as Neil Armstrong became the first man to step on the surface of the Moon.

America also watched in shock as Space Shuttle Challenger blew up shortly after takeoff January 28, 1986. The much-anticipated flight had captured the imagination and attention of millions of students who were anxious to follow teacher Christa McAuliffe on her unprecedented journey as a civilian astronaut. After a day of wide coverage across the three major networks and CNN, Peter Jennings presented this report on ABC’s World News Tonight.

► The McCarthy Hearings. I have written before about the role television played in broadcasting important Congressional hearings and investigations. The Communist witch hunt and in particular the McCarthy hearings in 1954 and the Watergate news coverage and hearings (1973) are two major examples of moving pictures becoming primary sources that continue to influence the historical record.

ABC’s unprecedented live broadcast of the McCarthy hearings (188 hours, 36 days) cost the fledgling network $5.7M in 2020 dollars. Media scholar Ben Bagdikian, who covered the hearings as a young reporter, says: “McCarthy was an important part of post-World War II history as television became a major instrument of American politics, with all of its sins and advantages.” The hearings “were the first demonstration of how melodrama in politics was made for television. The hearings were great drama, and television ate it up.” (Source)

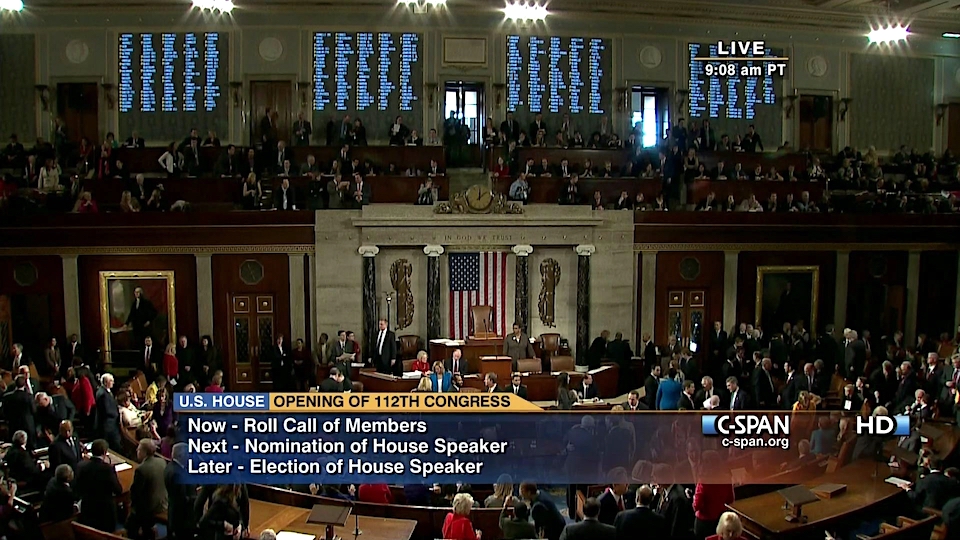

► C-SPAN. The premiere of C-SPAN (a service of the cable TV industry) in 1979 meant that “live” proceedings could now be seen in homes and schools via cable TV across the country. While C-SPAN has seldom achieved a large live audience, it has relentlessly captured Congressional and other policy and public affairs events “unfiltered” by analysis. Those same events are now archived and available for students and teachers. In the year after C-SPAN’s appearance, CNN launched in Atlanta and the 24-hour news cycle began.

What We Want Students to Know

Each of the events described here was captured by someone, and in many cases we don’t know the name of the photographer. (Students could begin researching to determine the circumstances surrounding memorable events and their documentation.) But capturing an event is one thing: distributing it is another.

When film footage of the Holocaust was taken, it had to be developed and then transported by plane where it would eventually be edited into a newsreel and then distributed (usually by freight truck) to theatres before being seen.

Years later, during the Vietnam War, footage would be transmitted by early information satellites (Telstar1 was launched in 1962) back to the US where it could be seen that day or the next. Today, photojournalists as well as our students take photos or videos that can be instantaneously uploaded to social media for all to see.

With the time between capturing the event and distributing the video down to minutes or even seconds, and given the internet’s power to rapidly spread live visual content around the world via social media, it becomes increasingly important for students to create their own mental “media filters.”

Help students learn to stop and consider these “critical viewing” and “media literacy” questions:

- who created the video and why?

- can I verify it?

- could there be something important that has been omitted and why?

- where can I go to learn more about this event?

- do other video recordings of this event exist? What do they show?

You can add questions of your own. Each question becomes the basis for a media literacy lesson. In a world where students get their news and information primarily from visual sources, it’s vital that they keep their brains in gear as they gaze upon the never-ending video stream of life on Earth.

Resources for Further Exploration:

100 Media Moments That Changed America (ABC-CLIO – Greenwood Press)

The History Channel Classroom (Archive of shows and footage from early years of THC.)

Primary Source Set: The Impact of Television on News Media (PBS Learning Media)

Television: A Guide to Resources: Primary Sources (Cornell University). A large selection of reference sources and databases useful for the study of television.

Resources for Moving Image Related Subjects & Materials (Library of Congress)

“Knowledge, Fear, and Changing Perspectives: The Impact of Using News as a Primary Source in Classrooms” (Social Education October 2018)

Up All Night: Ted Turner, CNN, and the Birth of 24-Hour News (Abrams, 2020). “This book shows how important it is to understand CNN’s history and backstory to fully appreciate where we are today in cable news and fast journalism.” – Soledad O’Brien

3 Black Photographers on Capturing the George Floyd Protests (Wired Magazine)

Frank maintains the popular Media Literacy Clearinghouse website (www.frankwbaker.com). He invites educators to follow MLC on Facebook and him on Twitter @fbaker.

The cameras role in documenting a critical social movement

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/the-cameras-role-in-documenting-a-critical-social-movement