Teaching U.S. History in Turbulent Times

Editor’s note: Lauren and Sarah are long-time contributors to our MiddleWeb blog Future of History. They both teach 8th grade U.S. History – Lauren in Chicago and Sarah near Los Angeles.

Their suggested title for this dialogue series: “Two white female teachers talking about teaching U.S. history in turbulent times.” See their bios at the end of the post. This is the first episode in a three-part conversation. Comments welcomed!

By Lauren Brown and Sarah Cooper

The protests that have been occurring across the country since the killing of George Floyd have led us once again to ask how best to teach U.S. history. These are issues that we have wrestled with throughout most of our careers, but recent events bring them to the forefront.

A traditional blog post – with just one voice – is challenging to write at the moment because it presumes that we have answers. We don’t. Instead, we decided to get together and discuss the concerns we both have as educators. What follows is the first of these conversations.

In an article I read recently, The emotional impact of watching white people wake up to racism in real-time, a Black woman journalist wrote that on one level, it was painful to her to see white people discuss racism because she felt that the freedom to do so has not always been granted to people of color.

Statements like that remind me to be sensitive. I am seeing in social media that Black educators want us, as whites, to do some of this heavy lifting for awhile. But this can also be perceived by others as, “Oh, you’re finally recognizing that this is a problem?”

As I personally worry and wrestle with the question of how people of color might react to what I say, I am recognizing that Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, might point out that this is not about me. But it is hard to let this go. I can’t help but admit that it matters to me to be seen as being on the “right side” of history, and on the “right side” of the equity work.

Yet I think that, especially as U.S. history teachers covering often sensitive topics, we do need to work through our own feelings before being able to teach effectively in this moment. It’s uncomfortable and important work, and I also often “screw it up.”

To this end, what I have been trying not to do lately is be defensive, to polish my merit badge of white woke-ness. You and I have similar backgrounds in that we both majored in American studies in college and have read books on antiracism and Black history for years.

At the same time, I think back to my own education, and, even as someone who focused on U.S. history for four years of college and two years of a master’s program, I see massive gaps. As one example, I had a total of two African-American teachers – in high school, college and graduate school. One professor taught one of the finest classes I took in college, a survey course of African-American literature that exposed me to a slew of canonical names I should have known before. In that course I felt like my world was busting wide open, gaps were filling in, connections cementing.

I think back, too, to the many white teachers who talked about race in deep ways – a professor who conducted a Gilder Lehrman graduate course on military and political emancipation; a seminal high school teacher who taught a senior elective on U.S. social history that made me realize that history needs to be told at a grassroots level.

What made these teachers so effective? They relied on primary sources to tell stories, they did not flinch from casting the U.S. in a sometimes negative light, and they emanated a belief that we can do better, that we will do better.

Lauren. I want to pick up on your point about teaching social history and using primary sources. I just watched a rebroadcast on 60 Minutes about the Tulsa Greenwood Massacre of 1921. What struck me most about watching this 14-minute clip from 1999 is an interview with a woman who lived through it (see minute 4:21). Hearing her talk about her prom dress makes it real to students.

But the rest of the episode, while informative for adults, left me cold. It is a clip I feel I could not show to students for a variety of reasons, but the main one is that it is missing the humanity. It doesn’t have the pathos. I think when we teach about these traumatic events in the past, our tone of voice has to have empathy and gravitas. Compare the 60 Minutes video clip that sounds like a matter-of-fact news story with the kind of work Ken Burns does in which the music and narration conveys a mood.

I recognize that this is where history teachers wade into murky water: the teaching of facts versus the teaching of feeling. I think this is a topic you and I are going to get into in another “episode,” so I’ll save that for now.

The one point I do want to make here is that we have to be cognizant of the feelings of the students in our middle school classrooms. Teaching about something like lynching or race riots has to take into consideration how emotional these topics are for students. And we have to recognize that they have different impacts based on the race of the student and on differences in personality among students, too.

We are responsible for teaching about traumatic events, uncomfortable truths, and stories that do not have happy endings. We have to be careful – in our rush to teach “the truth” about oppression and racism in United States history – of the trauma we may be inflicting on students, either because of the material itself or because it leaves students with a sense of hopelessness.

Sarah. How are we cognizant of the feelings of students in our classrooms? How do we know? I don’t know that we always do, and this concerns me. It makes me want to prioritize socio-emotional learning even more in my classroom next year through more frequent personal check-ins. And to create a classroom environment in which we share, talk and write about our communities – our shared campus community as well as the neighborhoods, families, religions, ethnicities each student comes from – in which we listen to each person’s humanity.

At the same time I never want to call out anyone if they don’t want to talk, especially if they’re the sole representative in the classroom of a group they belong to. This is a really difficult balance, so much that sometimes it feels I’m walking the edge day by day.

Lauren. I agree that the answer is we don’t always know and that’s why we need to be so careful. When students are uncomfortable, they don’t always tell us. Sometimes you can tell from body language, facial expressions, students who normally participate a lot becoming quiet.

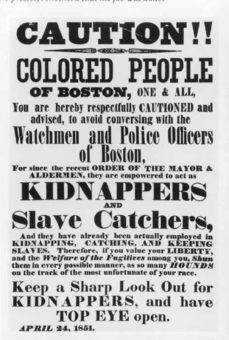

For instance, I would never show the video of George Floyd’s murder in class to eighth graders, just as I would hesitate to show especially brutal segments of Ava Du Vernay’s important documentary 13th. Yet, looking back in history, are less graphic political primary sources about enslavement, such as South Carolina’s “immediate causes” declaration of secession, sufficient to communicate what we need to show?

Lauren. That’s a great primary source, but I think I would pair it with something that is more personal. Something like a diary entry or letter that shows the “human” side of things. Choosing the right sources – ones that are accessible to a wide range of students, “cover” what we want to cover, show the complexity of whatever issue it is we are teaching, all while trying not to traumatize – is an exhausting task, but a necessary part of the work history teachers do.

In Episode 2 we continue this conversation about how to uplift while teaching about current and historical oppression, as well as how we’ve tried to handle pushback from parents about what can seem too intense or too “activist” in the classroom. Stay tuned and thanks for reading!

Feature image: “New Battle Now in Progress” Tulsa World (Yale National Initiative)

Lauren S. Brown (@USHistoryIdeas) has taught U.S. history, sociology and world geography in public middle and high schools in the Midwest. She currently teaches 8th grade U.S. history in a suburban Chicago school district. Lauren has also supervised pre-service social studies teachers and taught social studies methods courses. Her degrees include an M.A. in History from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her blog U.S. History Ideas for Teachers is insightful and packed with resources.

Sarah J. Cooper (@sarahjcooper01) teaches eighth-grade U.S. history and is assistant head for academic life at Flintridge Preparatory School in La Canada, California, where she has also taught English Language Arts. Sarah is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom (Routledge, 2017). She presents at conferences and writes for a variety of educational sites. You can find all of Sarah’s writing at sarahjcooper.com.

REPLY ON TWITTER: Chris Dransoff (@Dransoff) “The teaching of history is way overdue for major revamping on so many levels; content, methods, you name it. Many well meaning teachers out there, but academics in the field can’t agree on standards; want respect but are mired in a history of bad teaching of history. Need a reset.”