Teaching U.S. History Through a Trauma Lens

Their suggested title for this dialogue series: “Two white female teachers talking about teaching U.S. history in turbulent times.” See their bios at the end of the post. This is the second episode in a three-part conversation. Comments welcomed!

By Sarah Cooper and Lauren Brown

Sarah: In our first conversation, “Teaching U.S. History in Turbulent Times,” we left off by discussing which primary sources are most effective for conveying empathy and gravitas in history lessons. This leads into another topic that has gripped me lately: how to sufficiently teach about systemic racism and oppression without making this lens the only way students see history.

Lauren: I have felt that dread when teaching about lynching. I can’t not teach it because it is central to an understanding of the Jim Crow era, but it is so traumatic. A few years ago at the end of this lesson I saw one of my students, an African American girl, with tears rolling down her cheek. I took her aside, and we talked. Those tears forced me to realize that others might have held back their own tears while still feeling the pain. I needed to find another way to teach it.

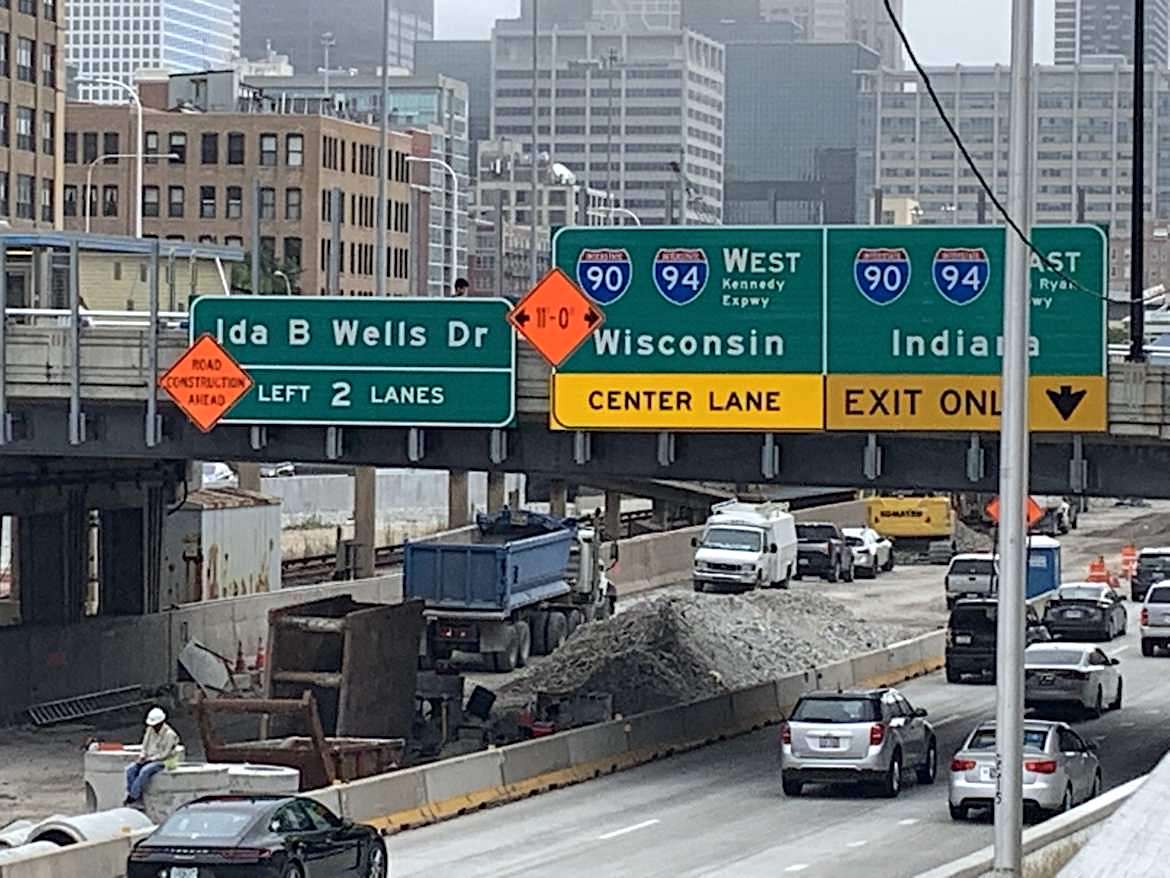

Just over a year ago, the City of Chicago renamed a major highway in honor of Wells. It is the street that students in my community exit onto as they drive into the city. Ending the lesson by explaining why Wells was honored in this way feels so much better. Recently, Wells was given a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for her reporting against lynching. These honors remind me of the power of public memorials, as our country grapples with controversy about Confederate and other monuments and the naming rituals of schools and colleges.

Sarah: Your story of the highway renaming makes a powerful connection to the present. Students need to know difficult history, but they also need a chance to notice positive change, and sometimes even step away from sadness and injustice entirely for a moment. I’m reminded of chaperoning eighth graders to Washington, D.C. early in my teaching career. After spending three hours at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in the afternoon, we followed up with an Orioles game. There’s only so much anyone can process in one hour, day or week.

Lauren: It’s interesting that you mention the juxtaposition of the baseball game with the Holocaust museum. I have noticed that timing the teaching of traumatic topics during the week before vacations, or right when we come back from a break has been helpful. The students are prone to goofing off at these times, but they don’t in my class because the topics are too serious.

Sarah: The weight of history can accrue heavily as the school year continues. I’m remembering that when I taught 11th grade U.S. history, it was hard to really exhale until we hit Reconstruction – and then the promise of Juneteenth quickly collapsed, and we were deep in history’s injustices again until we came to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and especially the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The sin of enslavement mars U.S. history from 1619 to 1865 and then all the way to the present in its after effects, even with moments of progress interspersed.

Teaching Tolerance’s fantastic Teaching Hard History standards emphasize resistance and resilience throughout, with statements such as “Students will recognize that enslaved people resisted slavery in ways that ranged from violence to smaller, everyday means of asserting their humanity and opposing their enslavers” and “Students will examine the ways that people who were enslaved tried to claim their freedom after the Civil War.”

Lauren: What a thoughtful way to phrase standards pertaining to slavery. Episode 6 of Teaching Tolerance’s podcasts gave constructive advice about teaching in the context of such resistance. This podcast makes the point that the very brutality of the slave system was partly because there was resistance.

Thinking about what kind of agency slaves had, the ways they survived, the ways they resisted both openly and behind the scenes can go a long way towards finding empowerment in the past and perhaps mitigating the traumatic impact of this history on our adolescent students. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum also has a helpful page of advice that applies to the teaching of anything oppressive and difficult, not just the Holocaust.

Yet I’m also realizing there is a tricky aspect to the standard you mention above. When we talk about resistance and the ways in which slaves managed to preserve cultural identity, it could be incorrectly perceived that we are suggesting the message should be, “See, slavery wasn’t so bad – slaves were able to resist, make their own music, establish their own understanding of Christianity.” Obviously, we don’t want to suggest that. But it can be a tricky balancing act, don’t you think?

Sarah: Yes. It’s almost impossible to achieve this balanced tone, and I don’t feel I ever hit it perfectly.

Lauren: Maybe we need to remember that reaching that perfect balance is also hard because our students are individuals. They will all react differently not just to the content, but to us.

Sarah: Absolutely. Sometimes I try to find a new way in, so that different students can take their own paths to understanding the material. One way to include uplift is through literature, music, art or stories that leaven the “hard history” we are teaching. For our study of The Hate U Give, Junauda Petrus’ essay “Can We Please Give the Police Departments to the Grandmothers?” from Maureen Johnson’s How I Resist: Activism and Hope for a New Generation lent an element of wish fulfillment and agency that the novel did not always show.

Lauren: I agree. The arts are not only powerful tools, but they have also provided ways for African Americans to tell their own stories in the worst of times. Certain poems and prose excerpts from Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston and others offer different perspectives of the Black experience.

‘Black Panther’ and the Revenge of the Black Nerds (NYT)

One of my favorite pieces to discuss with students is an excerpt from a chapter in Langston Hughes’s autobiography The Big Sea called “When the Negro was in Vogue” about the Harlem Renaissance. Maya Angelou’s poem, “Still I Rise,” though written 50 years later, is a valuable comparison piece to Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay, “How it Feels to be Colored Me.” So is this excerpt from a New York Times piece about the 2018 film Black Panther.

Sarah: What a great piece. It reminds me of a short story in the collection edited by National Book Award finalist Ibi Zoboi, Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America. It’s by Lamar Giles and the title tells it: “Black. Nerd. Problems.”

One last way I aim for uplift is to focus on people who have dedicated their lives to improving society, through a reformers project. After we look at social reform through a specific thematic lens, such as women’s history or the Progressive Era (problematic in its own way for its lack of true equality for all groups), students pick their own reformer to research. They often but not always choose someone who comes from the same background they do. Seeing the reformers’ photos on the wall, a gallery of the best of the human spirit, is one of my favorite parts of the year.

Lauren: So interesting that so many choose someone from their own background! I think this speaks to the importance of needing to see ourselves in history. My students do oral history projects later in the school year, where they have to interview someone in their family. One of the key parts of the assignment is to connect their family’s story to the “larger story” of U.S. history by connecting to themes we have been discussing all school year. They groan when I assign it, but I find they appreciate it when they realize their families’ stories are a part of history.

There are other ways we can do this, by being inclusive of the history of diverse racial and ethnic groups and genders. But sometimes I struggle with how to do this responsibly in ways that are meaningful and not superficial.

NEXT TIME: In our third and last conversation, we will discuss whether teacher activism has any place in the classroom, especially during an election year and during a time of great partisan divisions.

Feature image credit: Teaching Tolerance

Sarah J. Cooper (@sarahjcooper01) teaches eighth-grade U.S. history and is assistant head for academic life at Flintridge Preparatory School in La Canada, California, where she has also taught English Language Arts. Sarah is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom (Routledge, 2017). She presents at conferences and writes for a variety of educational sites. You can find all of Sarah’s writing at sarahjcooper.com.

Lauren S. Brown (@USHistoryIdeas) has taught U.S. history, sociology and world geography in public middle and high schools in the Midwest. She currently teaches 8th grade U.S. history in a suburban Chicago school district. Lauren has also supervised pre-service social studies teachers and taught social studies methods courses. Her degrees include an M.A. in History from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her blog U.S. History Ideas for Teachers is insightful and packed with resources.