Rigor Helps Kids with Special Needs Succeed

By Barbara R. Blackburn and Bradley Witzel

Barbara Blackburn

When you hear the word rigor, do you automatically assume that’s something students with special needs can’t do?

Sometimes we believe our students who are struggling – whether they have special needs, are learning in a new language, or are challenged by other issues – simply cannot learn at high levels. But if we look at the definition of rigor, we can begin to grow our understanding.

Bradley Witzel

In her series of books focused on teaching with rigor, Barbara defines it this way:

Rigor is creating an environment in which each student is expected to learn at high levels, is supported so he or she can learn at high levels, and demonstrates learning at high levels (Blackburn, 2018).

This definition supports the idea that students with special needs can learn at high levels. At times, they cannot answer even basic questions, so we accept that there is a limit to what they can do.

Realistically, all students are capable of rigorous work, as long as they have the right support and scaffolding. As Brad points out,

Just because a student is labeled learning disabled or at risk, it does not mean he or she is incapable of learning. Students with learning disabilities have average to above-average intelligence. Therefore, ensuring their success in school is a matter of finding the appropriate teaching strategies and motivation tools, all of which we can control as teachers.

Let’s look at four beliefs related to rigor and students with special needs that support our perspective.

1. Approach Teaching with a CapABLE mindset.

Do we believe that every one of our students with special needs is capABLE? Or do we focus on the label that they are disABLEd? Our perspective on those two words drives how we teach students. We either expect them to work at high levels, or we think they “are doing the best they can” as long as they try.

Other teachers put expectations to the side and focus on strategies that uncover ability. For example, Scott Bauserman, a teacher at Decatur Central High School in Indiana, asks his students to choose a topic from the social studies unit and design a game.

The finished product must teach about the topic, use appropriate vocabulary and processes, and be fun to play. As he explains,

Students have to construct the game, the [game] box, provide pieces and a board, and write the rules. I received a wide variety. One student game I will always remember was about how a bill gets passed into law. We spent time [in class] talking about all the points where a bill in Congress or the state General Assembly could be killed, pigeon-holed, or defeated.

But the student had cut trap doors at the points where a bill could be killed, and if a player landed on a trap door/bills stopper, the player to the right could pull a string, making that player’s token disappear from the board. The player would have to start over.

Not a bad game from a special needs student who has fetal alcohol syndrome and is still struggling to pass his classes.

2. Each Student Can Learn at Rigorous Levels

This is one of our foundational beliefs: each student is capable of rigorous work. Barbara was reminded of this a few years ago when she was in a school and met Gabrielle. Barbara’s favorite question to ask students is, “If you were in charge of the school, what would you change?” This student’s answer was insightful. Gabrielle said, “For people who don’t understand as much . . . [they should] be in higher level classes to understand more [because] if they already don’t know much, you don’t want to teach them to not know much over and over.”

Now you might laugh at her comment, but it is very true and insightful. Many students aren’t really progressing; they are learning variations of the same things, or they are not learning much at all. This is especially true for students with special needs included in a general education classroom.

3. Students Should Receive Quality Instruction Tailored to Their Needs

Part of rigor for students with special needs is providing support that is tailored to their specific needs. In the next section, we’ll provide a specific example of scaffolding, but now we’d like to take a “big picture” look at why we should customize support.

Let’s think about a grocery store. In larger stores, there are three options for checkout. Some customers go through the Express Lane since they have very few items they need. In this analogy, the “items” are the knowledge, understanding, and skills they need to go through the lane. The Express Lane is for more advanced students. They have fewer items to process since they have already mastered many or all of the skills.

The regular lane is for those who have more items to be processed – more concepts or skills they need to understand to be successful. It will take longer to go through the line because they will need additional instruction to help them.

Finally, there are times when the cashier calls the manager for an individual override on an item that needs special attention. In our analogy, these situations are for your students who need specialized help, perhaps individually or in a small group.

Everyone exits the store when they master the information, but at different times. In the classroom all students are successful with the same content, just at different rates. In this example, all students master rigorous work, but in different ways at distinctive times.

4. Rigorous Assignments Call for Appropriate Student Support

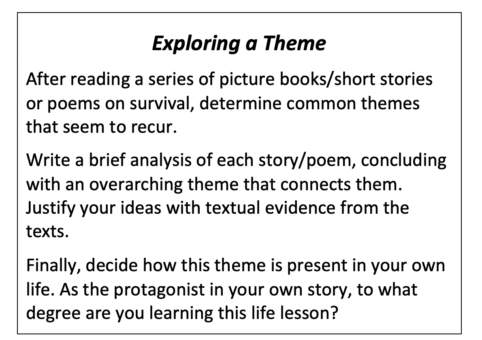

Too often, teachers assign a rigorous task, but assume that students with special needs need something “easier.” As we’ve just discussed, this is not necessarily true. For example, look at this rigorous assignment.

We believe students with special needs can complete this task, especially if they are provided with additional support. For example, guide students through a semantic feature analysis graphic organizer (here’s an example) after they read each picture book or short story.

Then lead a discussion, noting commonalities and differences in plot, characters, conflict, etc across your collection of texts. Students can use an organizer to write their analysis. You might also use a paragraph frame if needed for additional support.

The organizing and framing tools provide the scaffolding support that helps you empower students with special needs to tackle rigorous classroom work.

A Final Note

Helping students learn at rigorous levels begins with our belief they can do so. Then you can expect high levels of learning and support them so they achieve your goals.

Bradley Witzel is the Adelaide Worth Daniels Distinguished Professor of Education at Western Carolina University and has worked as a classroom teacher and a paraeducator with high-achieving students with disabilities. He has written nine books and over 50 other professional publications, developed over 20 multimedia resources, and delivered over 500 presentations and workshops.

Barbara and Brad are the authors of Rigor for Students with Special Needs, 2nd edition from Routledge/Eye On Education.

Hi! This is Scott Bauserman, the teacher mentioned in the story. I am glad to see that story being used. It was an important lesson to me as an educator that gets at exactly the point you are making: Students always know more than you think and can easily measure. Rigor is defined student by student.

Regards!