This Personal Challenge Rejuvenated My Career

When multi-book author Marilyn Pryle first learned about National Board Certification, “I was a dedicated, informed, well-liked teacher in the prime of my career. But was I really reaching the highest levels of effectiveness and accomplishment? I wanted to find out.”

By Marilyn Pryle

There were ways to improve, topics to study, and experience to be gained, but there was no “next-level” advancement that I could sink my teeth into – or so I thought. About 10 years ago, an opportunity was given to me that changed the trajectory of my career.

One day my principal announced to our faculty that the district would support anyone who wanted to try for National Board Certification. I had no idea what that was, but I was intrigued. At the time, I’d been at my district for four years, and I had been teaching for about 12 years. My district did not offer any stipend for being National Board Certified, and no one had ever tried it.

But I was interested. The thought of examining my teaching in real time, of really looking at my practice in motion and finding evidence for what I thought I was doing, sounded like an exciting challenge.

I already had two master’s degrees: one in Reading Education and one in Creative Writing. But National Board felt different. Through my own classroom assessments and student feedback, I knew my teaching was at least somewhat effective. I knew I was working hard and searching out best practices. I was a dedicated, informed, well-liked teacher in the prime of my career. But was I really reaching the highest levels of effectiveness and accomplishment? I wanted to find out.

Investigating the process

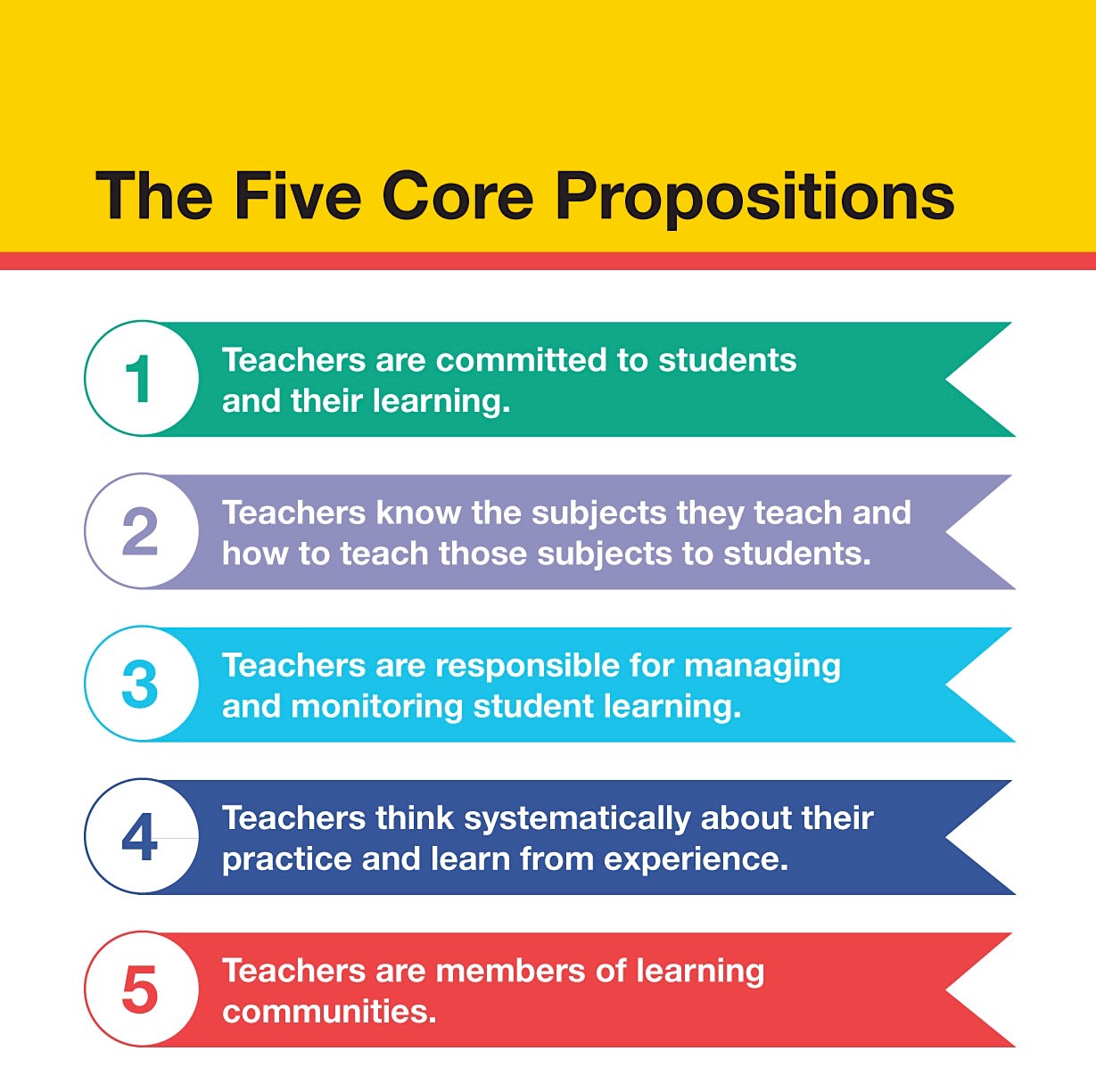

When I looked at the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards website, I was immediately pulled in by the 5 Core Propositions. These are ideas that I already felt strongly about and aspired to be even better at: I was committed to my students and passionate about my subject; I was completely invested in the students’ learning; I was, at that time, starting to think deeply about the systematic aspect of my practice; I wanted to be even more fully engaged in the community of teachers, both at the local level and beyond.

As I began to explore the National Board process, I was impressed by the emphasis on self-evaluation. I would be creating a portfolio of evidence. This would mean that I could choose what I wanted to focus on, highlight, and examine. I could fulfill the rubrics in the ways I thought best reflected my efforts and beliefs. This, I thought, mirrored good teaching.

National Board Certification is standards-based, job-embedded, self-directed professional development that is judged by a jury of your peers. – Rosalie Dibert, Pennsylvania educator and former NBPTS governing board member.

I also liked that National Board was created by teachers, and that my portfolio would be assessed by teachers. This was refreshing, and I felt empowered. So often, teachers are rated and ranked by systems and superiors who are far-removed from the classroom.

Here was a space built and maintained by teachers themselves. It felt like I was being told: “As teachers, we know what we are doing, and we know how to help each other grow and improve our craft.” I was inspired. This was the next step I needed.

Support makes a difference

From the beginning, I was given support. Through a grant, my district covered the application fees. In addition, a regional university offered credits for the process, and provided a teacher-mentor for me and the other teacher from my district who wanted to try.

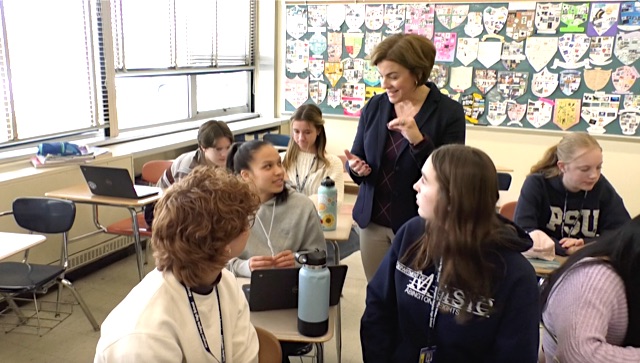

We met weekly after school, and our mentor helped us understand the Core Propositions, the Standards, and the requirements for the portfolio, including making and reflecting upon videos of our classroom teaching.

The mentor’s support was invaluable. As everyone knows, the National Board process is extremely rigorous – that’s why it’s so respected in the profession. Having someone to shepherd me through it definitely helped.

Evidence of impact

As I said above, I already had two master’s degrees before embarking on the National Board process. I realized that although I loved grad school, studying and theory, all of that was a kind of front-loading – there was never any post-teaching check to see if any of that information actually affected what I was doing with students. Deep down, I thought it must be having an impact, but could I prove it? Could I show the evidence?

Evidence is at the core of the National Board process. The search for evidence forced me to examine my assumptions and document my conclusions. And I found the answers to be mixed.

Yes, my class was student-centered, and my videos proved that. I had attended conferences, made in-house presentations to my colleagues, and mentored other teachers. Of course I couldn’t just say that I had done these things; I had to produce conference badges and presentation notes. But more than that, I had to process these experiences, as well as my classroom videos. What were the choices I was making in the moment? How did each portfolio item I completed demonstrate my growth as a practitioner and thinker? What would I do differently?

Download a 5-page Quick Guide to

the National Board Certification process

And there were gaps, real blind spots that came to light. I wasn’t differentiating as much or as deeply as I had thought I was. In addition, I wasn’t interacting with families as often or as meaningfully as I could have. As I uncovered these and other areas where I needed to improve, I reflected on how I could shore up my efforts.

For National Board Certification, one doesn’t have to prove that they are a perfect teacher; one only needs to be honestly reflective about shortcomings and demonstrate a commitment to continuing improvement. It requires presence, humility, patience, and authenticity.

The portfolio criteria and prompts guided me through. The National Board process not only gave me the space to reflect; it taught me how to reflect in the most meaningful way to effect change.

Changes in practice

I made some changes to my classroom during the process which became permanent. I found ways to incorporate more flexibility in my activities and assignments to allow for more differentiation. I began calling home with good reports and compliments instead of only for disciplinary or failure concerns.

I also made my classroom and activities more tactile and kinesthetic. I looked at the parts of my practice that were less student-centered and asked myself how I could make them more student-centered. I incorporated more acting, more art, and more music. I rearranged my room to include more flexible seating. I asked myself and my students how I could give them even more choice in their reading, writing, and expression.

My story is far from unique. Newly minted NBCTs consistently report that the experience was profound and the best professional development of their careers.

What the research says

The research on the effectiveness of National Board Certified Teachers (NBCTs) is abundant. One study showed that students taught by an NBCT are 1-2 months ahead of peers who did not have an NBCT. Another showed that kindergarten students taught by an NBCT are 31% more likely to achieve a proficient score on the state Kindergarten Readiness Assessment than other students. And another estimated that students who had just one math NBCT in their high school career could increase their lifetime earnings by $48,000 (Imagine if students had more than one!).

One statistic that personally resonated with me was about teacher longevity: NBCTs leave the profession at only one third the rate of all teachers who leave. I live in a state whose number of resignations hit a 10-year high last year – 9,600 teachers resigned in Pennsylvania in 2022. I find the NBCT retention rate incredibly encouraging, and not surprising.

I myself have had opportunities to leave the classroom, but I simply have not wanted to. The National Board process bonded me to the profession in a way nothing else had, and it continues to do so. I feel a level of commitment and responsibility to the students and the profession that I am not ready to end.

Examining equity and opportunity

Ten years ago, I was lucky: I had a one-time district grant that covered my initial certification fees. If those fees weren’t covered, I probably would not have engaged with the process. Last year, when I renewed my certification (called Maintenance of Certification), I had to pay out-of-pocket. My district does not offer a stipend for renewing Board certification once it is obtained.

What I’ve learned in speaking with many other teachers, both certified and not, is that in most states, the fee coverage and/or post-certification stipend varies widely from district to district. In one district, a teacher could receive full fee coverage and a large annual stipend; in another, one could receive neither.

This seems incredibly unfair – don’t all students deserve to have teachers who have proven they are deeply committed and distinguished in the field? Don’t all teachers deserve the chance to attempt this top-level form of professional growth and accomplishment – and to attempt it as many times as they need?

At the same time, I realize that districts are struggling and we cannot simply mandate district-level funding and stipends. The solution, then, must come from the state. Several states have successfully implemented system-wide incentives. Maryland, for example, covers the certification fees and awards a $10,000 salary increase for those who certify. What’s more, the state gives an additional $7,000 to NBCTs who teach in a designated high-need school.

This kind of commitment from a state helps ensure that the most vulnerable students get some of the best teachers. Stacie Marvin, NBCT and currently an Einstein Fellow in DC, moved from her school into a designated high-need school because of this incentive.

In Texas, NBCTs can receive a $3,000 to $9,000 pay increase, depending on their school’s population and rural status. This resulted in a nearly 750% increase in National Board applications. In California, NBCTs who teach in high-priority schools receive a $25,000 stipend over five years. This quadrupled the number of teachers in high-priority schools who pursue Board Certification. In addition, over half of the teachers receiving the California incentive are teachers of color.

Some closing thoughts

I will never forget the first surge of pride I felt when I learned I had achieved National Board Certification. That feeling has never diminished. Being an NBCT grounds me in confidence about my effectiveness and solidifies my dedication to the work.

In a time of unprecedented teacher criticism, burnout, and flight, National Board Certification provides an opportunity for teachers to feel empowered and inspired. We must demonstrate for future and new educators that – similar to other professions with board certification – ours has a next level to aspire to, one that is rigorous and deserves recognition and reward.

We must provide a space for mid-career growth, a profound experience that invigorates and recommits veteran teachers so that they stay instead of leave. And we must give every child in our country, especially the most vulnerable ones, the opportunity to be taught by a master teacher. It’s time to make National Board Certification accessible for all.