Why Reader Response Is So Important for Students

By Brenda Krupp, Lynne Dorfman and Aileen Hower

Brenda

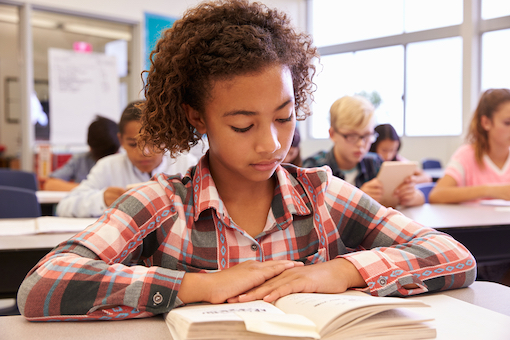

Most of the time, when readers engage in reading a text of any kind, their thinking is silent and invisible.

What is actually happening is that they are engaging with the text and almost immediately making a personal connection, thinking about what the text has to do with their life (past, present, and future) in some small or large way.

Readers can always make some kind of personal connection since most texts describe the lives of others, real or imagined, and readers have a need to respond to what they read. The act of a personal response to text is a big part of leading a readerly life.

Inviting Students to Respond

Lynne

When we invite readers to share and reflect on what they are reading, they develop a spirit of curiosity and an appreciation of the text’s messages. Discussions and written responses give rise to student voices, allowing them to acknowledge their connections and thoughts and have ownership over their reading processes.

Personal response elevates their reading because it asks students to think about text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections (Keene & Zimmerman, 1997). It also encourages a dialogue, of sorts, between the reader and the author – a conversation about what is being shared, as opposed to a one-way dissemination of information.

Reader response also keeps readers engaged and focused on reading. It’s a way of helping students to actively participate and keep their focus (Tovani, 2000). We want our readers to:

- remember what they’ve read,

- be able to ask thoughtful questions about the content of the text, and

- think about the impact and value of the information they’re gathering from the text.

Formulating a Written Response

When students are asked to respond to independent or assigned reading, they can consider several questions to get them started. These are open-ended and often high-level-thinking questions that prompt readers to express personal thoughts and feelings, make real-life connections, and explain individualized meaning-making responses about the text.

In their responses students can consider how the text confirms their worldview or how it differs from it. It could be about their beliefs about what is right or wrong or what it means to be human. In nonfiction readers can consider “What Surprised Me?”; “What Did The Author Think I Already Knew?”; and “What Challenged, Changed or Confirmed What I Already Knew?” (Beers & Probst, 2015), to more fully engage with and respond to the content they’re reading.

Sometimes we find that a text has changed us in some way, providing an epiphany. Characters in books and their actions often help readers to form and maintain their moral compass. Readers can use characters as role models and their stories as ways to set personal goals and make some changes in their lives.

Or readers might view a character and their actions as a cautionary tale that can influence their future actions. Quotes and examples from the text are helpful and work to support the reader’s thinking. Using a written response, readers can agree with or challenge the text, discussing points of agreement or challenge. The reader can ask themselves, “Did the text persuade you to change in some way, big or small? How so?”

What about the things a reader cares most about and considers to be important? Here, a reader can look at their own family, the groups they belong to and identify with, their cultural and social backgrounds, or their faith. Does this text make the reader care deeply about their community? Their traditions? Their place in the world? How does the text challenge the reader’s beliefs or confirm the reader’s place in this group?

Writing out a response like this often challenges the reader to first identify beliefs and put them into written form. The response goes deeper when the reader can engage their view points in light of what they have read and support their thinking with the text.

This questioning routine is great practice for the text-dependent questions students will be asked to respond to throughout their educational career. For example, this type of written response activity will help them prepare for high-stakes writing assignments. Through regular practice, responding to a central message and drawing upon the text to support their thinking will become more natural.

Did the text provide many opportunities for readers to connect emotionally? Readers can talk about the text for its value to keep them reading, to laugh, to cry, to sigh. Is the text entertaining, a work of art, a text to be read and reread?

During discussion or in writing, readers can voice their overall reactions to the text. Would they read something else by this author? Why or why not? Who do they believe is the intended audience? To whom would they recommend this text?

When Should We Shift to Response?

It is not always necessary to ask students to respond in writing. Just like it is not always necessary for students to work towards a pizza party or other prizes as rewards for reading (Marinak & Gambrell, 2016).

The biggest reward we can give our readers is time to have conversations about the books they are reading, to share their thoughts, feelings, and insights with others, to ask questions, and to offer their opinions and recommendations.

In Welcome to Reading Workshop, Brenda and Lynne express their belief that students should be spending most of their independent reading time reading, and some of their time responding to their reads in authentic ways. Conversations can occur during the reading of a text – often this happens in partnerships, literature circles or book clubs – or when a text is completed.

Sometimes students can respond before they read. Teachers can use frontloading strategies to build concepts and background knowledge, leading to a deeper understanding of the text and greater engagement.

Collaborative writing opportunities before, during, and after reading can increase students’ creativity and understanding of writing expectations and lessen anxiety about producing a “solo” written response. Students learn how to write for the reader when they share their writing with others.

Encouraging readers to stop and think during the reading of a text can:

- help readers identify misconceptions or problems they may be encountering,

- give readers time to consider the plot and what they know,

- allow readers time to process their feelings so far, and

- invite the reader to be actively engaged as they read.

Because we want most of the reading time to be spent on reading, encourage readers to use sticky notes to hold a place where they want to return and respond to what was written.

Brenda had a student who would often respond when the text surprised her or challenged her. Her thoughts were insightful. She enjoyed thinking through the text on paper, but she wanted someone to read her response as well. Responses can lead to conversations with peers and help teachers confer with students in meaningful ways. Students can make predictions and read to either validate them or change their predictions based on the information they have gleaned from the text.

While reading a text is a time for vocabulary self-selection, we can help students explore new words through illustrations, antonyms and synonyms, and by offering a definition in the words they would use.

Limit after-reading responses to authentic possibilities. They can be oral or written. Sharing the book with friends in a short recommendation or review to post on a special bulletin board or on the class website is a great way to respond! Here is a chance for the teacher to respond as well, offering suggestions that may lead students to examine new perspectives or nudge them in new directions.

A graffiti board is also a great place for readers to share their thoughts, opinions, feelings, and questions about what they are reading. Most of all, we want to create an environment where before, during, and after reading response feels natural and desirable.

What We Want to Remember

Responding to text can take many forms. As teachers, we want to encourage sincere, honest responses where students share their thoughts, feelings, opinions, and insights, just like we want for our own reading lives. While this is often done with pencil and paper, do not discount the laughter you might hear or the tears a child wipes away when a beloved character has passed. A sigh at the end of a beloved book is a form of reader’s response.

We want to remember that reading should be a joyful experience whenever possible. Allowing students to work together to write a single response or share their responses with a partner(s) builds confidence and excitement as readers talk about their reading discoveries with others.

Dr. Lynne Dorfman has a reading specialist certificate from LaSalle University and a doctoral degree in educational leadership from Immaculata University. She spent 38 years in Upper Moreland Township (PA) School District as a classroom teacher, a teacher of gifted education (K-5), a writing coach, a literacy coach and reading specialist, and a staff developer.

Brenda Krupp received a Master of Education in Curriculum & Instruction from Penn State University and a Bachelor of Science in Education from Temple University. She taught third grade at Franconia Elementary School for over 25 years, also served as teacher-on-assignment, coaching teachers in reading and writing practices.

Brenda was co-director for the PA Writing & Literature Project for many years and has also facilitated various courses in the teaching of writing, consulted with school districts on teaching writing (k-5), and served as a member of the Writing Project state network. She is co-author, with Lynne Dorfman, of Welcome to Reading Workshop: Structures and Routines That Support All Readers.

Dr. Aileen Hower is an Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator for the M.Ed. in Language and Literacy Program at Millersville University in Pennsylvania. She also is Coordinator for the Early Childhood Education Online Degree Completion Program. Aileen has presented at PCTELA, KSLA, NCTE, and ILA and facilitates the summer institute on reading and writing at Millersville University each year.

Aileen has been President of the Keystone State Literacy Association and currently serves on the executive board as the KSLA ILA Coordinator and is co-chair of the Keystone to Reading Secondary Book Awards. She is working on a book for ASCD on student reflection across the day with Dr. Persida Himmele, Dr. Lynne Dorfman, and Mrs. Catherine Gehman.

I love how it encourages personal connections and discussions about the text. Creating an environment where students feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and ideas is important. Plus, the practical tips for incorporating reader response activities are super helpful.