President vs. Press: A Media Literacy Challenge

A MiddleWeb Blog

The media dependence on politicians goes beyond the stream of content that politics provides. Broadcast, digital and print media rake in millions of dollars in ad revenue during election campaigns. After elections, the business of government continues and provides a major ongoing focus (and source of revenue) for the media, particularly when political actions and policy debates become controversial.

Students should understand what’s going on

How the media functions, and how it covers the White House, is important for students to understand. That is underscored by The Center for Civic Education’s National Standards for Civics & Government: “(students should) evaluate the role in American politics of television, radio, the press, newsletters, data bases, and emerging means of communication” (Source)

Do your students understand the role of the media? Can they define and identify the news media in their community and in their world? Do they know what it means to “cover the news”? Do students understand the role of the journalist and how they go about doing their jobs?

What do young people think about what they read in the news and how do they know who/what to trust? These are important “media literacy” questions for your students to consider.

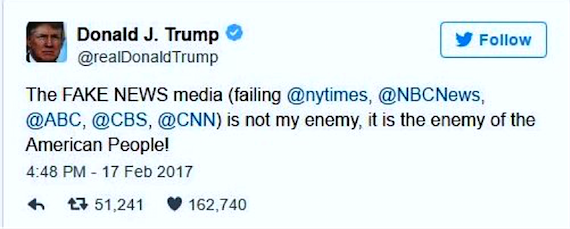

The enemies of the people

President Trump recently declared that the media were “the enemies of the American people.” Was he talking about all of the media (radio, TV, newspapers, bloggers, etc) or just a few? His tweet seemed to point fingers at a few, but they are some of the most prominent and influential.

In various statements, social media comments and one notable press conference, President Trump has named other media outlets as enemies, often in the wake of negative coverage (a Washington Post analysis in February described his criticisms as “inconsistent.”)

During the campaign for the presidency he frequently pointed to members of the media and called them “fake news.” (See this lengthy list of those attacked as of 10/11/16.) He has since reiterated that phrase many times. Thanks to this USA Today article, we know that repetition is one of the techniques of persuasion in propaganda.

Fake news was cited recently, in a survey by CommonSense Media, as one reason young people don’t trust the media.

Thomas Jefferson famously said: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” Would our students agree?

Writing in The Atlantic, Jon Finer concludes “(Trump’s) assault on the press seems calculated not to influence coverage, but to destroy the credibility of the media so he can usurp its traditional role as the arbiter of facts on which policy decisions are based.”

Implications for classroom instruction

One of my college-based media literacy colleagues described the strategies the new President has been using as: “Attempts to undermine knowledge, evidence, and facts is antithetical to being both a student enrolled in a college class, and an educated citizen in a democracy.”

Students who pay attention to what the President says should be employing some critical thinking strategies when they read, listen and watch. One particularly good media literacy question here is: what techniques is the media messenger using to make a message credible or believable? Just because the President (or his designee) says something, does that make it true? How do we find out?

Are your students aware of the non-partisan fact-checking web sites (now working around the clock) whose job it is to tell us when the President (and other media influencers) state facts or make declarations that are untrue? This would be a good time to introduce them to Snopes.com; FactCheck.org, and Politifact.com.

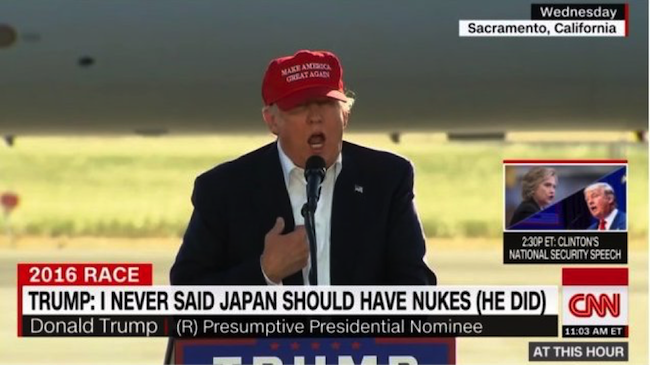

The news media have also been employing new strategies to challenge statements by the present administration. During the campaign, CNN regularly disputed Mr. Trump in its on-screen visuals:

Unprecedented media behavior

It’s clear that the journalism community has been challenged by the President’s repeated declarations that go against conventional wisdom and fact. It’s unusual to see the mainstream press openly and routinely challenge a President’s veracity. Yet this is currently happening daily in print and on television.

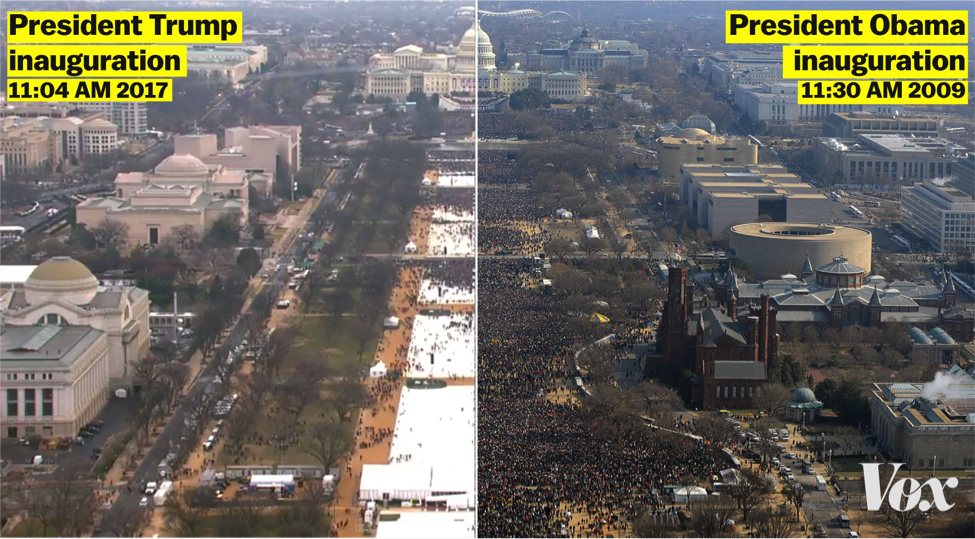

On the first day of his Presidency, Mr. Trump declared that the crowds at his inauguration were the largest ever. Photo evidence comparing the crowd size on the Washington Mall with those at President Obama’s made it clear that he was incorrect, and many news organizations pointed out that fact. But the president did not admit he was wrong; rather he called the media “dishonest.”

More recently, Trump accused former President Obama of orchestrating wiretapping activities inside of Trump Tower in New York City during the final weeks of the presidential campaign. Despite demands for evidence from both the media and Congress, no substantive evidence has been offered by Trump to date.

As a result, once again, normally circumspect media outlets have openly questioned whether the President is telling the truth and/or relying on sources that lack credibility. (On 3/12/17, Republican Sen. John McCain told CNN he has “no reason to believe” Trump’s allegation.)

Teaching suggestions

► Given the intensity of the current conflict between the Presidency and the Press, it seems worthwhile to task media literacy students with examining the way the news media is reporting misstatements by President Trump. For example, look at these two headlines:

BuzzFeed:

“Trump Falsely Claims Millions Voted Illegally, Costing Him The Popular Vote”

Associated Press:

“Trump wrongly blames fraud for loss of popular vote”

Students could compare and contrast how the media (in this case how a social media company, Buzzfeed, and a respected, time-honored news organization, the Associated Press) used different words in their headlines.

Locating headlines, and subsequent news stories like these, is not hard to do. For example, I regularly use the Google news aggregator, which displays multiple stories about current news topics from a variety of sources.

► Students could also be assigned to read, watch or listen to one news source in a given week, following how that source reported on a specific story. Coming together at the end of the week, they can report on their “content analysis.”

For example, did Fox News describe an event or a speech the same as MSNBC? Did The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times describe events identically? How and why does their reporting differ? Can students detect any bias on the part of these and other news organizations? In these situations, helping students distinguish among news reporters (e.g. NBC Nightly News) and news commentators (The Rachel Maddow Show) may be important.

► You might also encourage your students to contact the journalist or commentator (via email or social media – many reporters are now readily accessible on Twitter) to ask questions about their word choices in a story and/or other questions related to covering the Presidency. (Keep in mind that reporters seldom write the headlines for their print or website stories – editors usually do.)

It’s up to educators

In a 21st century world, with many sources for news and information, it’s challenging (and sometimes uncomfortable) to teach media literacy. But it is more important than ever that our students employ critical thinking/viewing and media literacy skills when they consume the news.

Giving your students opportunities to study what emanates from the White House, and how the media covers it, is an valuable 21st century college-and-career ready skill. I hope you will consider taking up this challenge.

Additional resources

► The Press & The President: A History. (radio/audio, WNYC, 11 min.)

► The Complicated History Between The Press & The Presidency. (Smithsonian Magazine)

► The Press, The President and the Danger Zone. (Bloomberg article)

► The Press & The Presidency. JFK Forum, Harvard University. (video)

► Newseum: The Press & the Presidency. This PDF was designed as support for class trips to the Newseum in Washington, D.C. It includes some pre- and post-visit activities that can be adapted for non-visiting media literacy classes as well.

► Smithsonian & The History Channel. Communicating The Presidency: The Media & Public Opinion (Lesson materials for grades 7-9)

► dml central. The Importance of Media Literacy in Partisan Times (infographic)

__________

Frank Baker’s book Political Campaigns & Political Advertising: A Media Literacy Guide (ABC-CLIO) was written to provide middle school students background on the role of the media. Reach him via email at fbaker1346@gmail.com