Using a Daybook to Promote Student Writing

This year you’ve resolved to incorporate more writing into your teaching day. Yes! This is the year that regular, low-risk, high engagement writing will become a daily habit for all of your students, whatever your content area, grabbing their interest and revealing to them the powerful write-think-learn connection.

But how to start? What supplies are needed? How will you manage all the written thought? What will inspire the students? Daily writing can be a big challenge, but if change is to occur, the first person in the room who must shift is the teacher.

Writing with your students

Establishing routines means changing ourselves first. But it’s not hard to start forming the habit now—today.

When students write, take the time to write with them—first to share your writing in all its messiness with students, and then to make sense of the intense interactions of a teaching day. A teacher who writes with her students is a teacher who understands the challenges in getting words right.

Coaches of sports have played the game first. Drawing on their personal experience, they can offer reliable tips for improvement. Get in there and run the drills with students. You’ll be better able to help them.

Build the daily writing in

Remember to include daily writing when you make your lesson plans. Employ good teaching decisions about what you want to add to the student-created text. Despite our need to have workable advance plans, this is a place where simply knowing that your students need to write will lead to exploring avenues to help them do just that.

Daily writing has become a habit with my students, thanks to three simple steps:

- Ask students to purchase a notebook that’s dedicated to ideas and personal reflections.

- Have them number every page so they can organize and index what they write (see below).

- Offer a quick prompt each day to keep them in the habit of writing.

Absent any other plan, work a “stop and think by writing” pause into nearly every lesson, followed with lots of sharing of ideas. Additionally, your routine will provide students with valuable time to absorb and apply lessons. Before you know it, you and your students will be writing volumes.

The best way to form a new habit is to just get started. Follow the daybook steps I describe below to get both you and your classes going, and then experiment with writing as you travel together through the curricular year.

Introducing the daybook requirement

Some office supply stores have entire walls devoted to unique journals. It’s a great place to stand and wait for the journals to start speaking. Other general merchandise stores routinely place notebooks on sale that can be found as cheaply as 50 cents. I frequent these and watch for back-to-school sales so there is always a pile of extra notebooks stored in the room.

Emphasize that the student can spend as much or as little on the book as they choose, but that they must find a book that speaks to them. And what does the book say? It says: Write in me. You know you want to.

The focus for the first daybook mini-lesson is to emphasize finding the right book, not what it is or how it is used. The students are only told that they will be expected to write in the book daily and should shop with an eye to finding something that matches their style and preferences. What will make you want to write? is the determining question.

Another feature of the chat on school supplies is finding the right writing utensil. Students consider: What’s your favorite pen? Do you prefer pens or pencils when you get to choose? Lined or unlined paper? Are you a doodler?

TEACHER TIP: Show the class the student-created dramatization available on You Tube of Taylor Mali’s poem “On Girls Lending Pens” to get a discussion of school supplies going. This humorous poem also sends the subtle message that even the most mundane can be the topic of a writing piece.

I first confess to my enduring love of shopping for school supplies. All those blank pages look like a literal clean slate and the hope that “this year might be different. No mistakes have been made yet, and my future is currently a blank page.” Generally, my confession flushes out the school supply nerds, and a lively discussion encourages those enthusiasts to wax poetic on finding just the right tool to make schoolwork individual and enjoyable.

Why spend so much time describing the notebook?

Helping students surface their idiosyncratic writing process is one of the objectives of the daybook, so spending time on the physical requirements for a creative process is not frivolous. Defining a personal heuristic and connecting that to their own creative experience becomes a reflective activity as the course proceeds. I want students to think about how their choices influence their motivation to write.

Here are my criteria for a daybook:

-

Must make you want to write!

- Must be 5×7 or larger.

- Must be portable so it can be carried at all times.

- Can be lined or unlined—your choice.

- Spend as much or as little as you like.

- Make it your own. Some students add art to the cover. Some collect artifacts.

- Number every page.

The final directive is an early homework assignment to number every page. At this point I model how I have numbered all the pages of my current, unsullied notebook, the one I will use along with my students throughout the term. Pages are numbered like a book, front and back on either the top or bottom right- and left-hand outside corners.

I, too, have purchased a distinctive notebook for the express purpose of writing with my students as we go through the term. I also share previous daybooks from my stack of them so they can see that it isn’t hard to do a lot of writing in a term.

Finally, set a due date for bringing the daybook and a favorite pen or pencil to class. Until your due date arrives, remind students daily that they need the daybook because we are going to get started writing on that day.

Number all the pages

The daybook is intended to be exclusively reserved for student thoughts and explorations in writing. Numbering the pages has a surprisingly positive effect on helping students preserve this book for that exploration. Pages do not get torn out and used for other classes.

Writers write about what engages their minds, responding to the world around them. The daybook is a place for brainstorming on topics that attract our students’ interest. Numbering pages helps students keep track of their evolving viewpoints on individual topics.

From numbering to indexing

For teachers who have tried to use journals in the past but were unable to take them beyond a daily writing activity which went nowhere, the page number is the organizational feature that tracks writing for later use. For instance, when I plan a writing assignment, several pre-writes or brainstorms are built into the process. By showing students how to index those writings on the last page, students can see how they are building their thinking around an assignment to come.

In my senior English classes, all students write a Personal Statement early in the course. This assignment is useful for post-high school plans like college or work applications. (This is easily adapted to middle school.) Before they write the first draft, we do several daybook entries to collect thinking about the values, skills, and talents they possess.

STUDENT COMMENT: “It was a struggle at first, to begin writing ‘free’ pieces. Then I realized that I have so many thoughts that I have never written down. Writing became so much more fun…I am so incredibly glad that I was given this chance because now I love writing stories!” – George

After the first entry for this assignment, I model how to start building an index on the last page of the daybook. They title the index entry “Personal Statement” and then begin to record the pages where they have written about themselves. Later these can be accessed for the first draft. This has proven to be the most expedient and easiest way to make sense of continual writing.

The process of collecting student writing chronologically means you don’t need to figure out and categorize all the writing students will complete in advance of beginning a course. Just begin! Later students can search their entries for pertinent ideas and notes around a topic. Categorization of material is another skill students practice as they build their index.

Open the daybooks and begin!

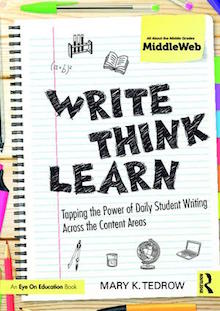

With the notebook and the format set up, you are ready to enact your plan to incorporate student writing into every lesson. To learn more about the big picture of daily writing, see my earlier post here at MiddleWeb, “Make Writing a Daily Ritual in Every Content Area,” or check out my book Write, Think, Learn: Tapping the Power of Daily Student Writing Across the Content Area.

______________________

Tedrow’s book Write, Think, Learn: Tapping the Power of Daily Student Writing Across the Content Areas (2017), is published by Routledge/Eye on Education in partnership with MiddleWeb. Receive a 20% discount with coupon code MWEB1.

Superb! I very much appreciated the important tips shared here.

I love the idea to make a book for my students and myself to write our thougths.