Why History Classes Need Vocab Lessons

A MiddleWeb Blog

Part of the assignment required students to discuss major themes in the excerpts. I read the following in a student’s paper.

The author of All Quiet on the Western Front was trying to say that war was really bad.

I sighed. Well, yes. Of course this is the major idea. But really? This was all the student could come up with? And then, the epiphany, when I read another student’s paper:

The experience of war was so devastating that it destroyed the lives of young men.

I had a similar insight when grading a writing assignment about the rise of city bosses and political machines. Students had to address the question of why city bosses flourished during the transitional time of urban growth before the Progressive Era. Again, I would get sentences like,

City bosses helped poor immigrants because conditions in tenements were really bad.

True, conditions were “really bad.” But isn’t there a better way to say that?

And then I overheard my students whining about their vocab test in Language Arts class. Gavin was complaining to a friend that he kept forgetting what “squalid” meant.

“Tenements,” I interjected.

“Huh?”

“Squalid. Do you remember the Jacob Riis photos I showed you in class yesterday of tenements? Weren’t the conditions in those tenements squalid? Would that help you remember the word?”

Since then, I’ve been working with the L.A. teacher to collaborate on what words might be useful in my class. This gives students reasons to use the words, not just memorize them for the L.A. test and then forget them.

“Why do we need more words?”

Students often whine about vocabulary tests. They just don’t see the point about memorizing a bunch of words that to them just mean the same thing as other words they already know. “Why do we need to know squalid,” they ask. “Can’t we just say dirty?”

But the tenements weren’t just dirty. They were, according to one definition of squalid, “extremely dirty and unpleasant, especially as a result of poverty or neglect.” This seven-letter word speaks volumes about the conditions of the urban poor at the turn of the century in a way that “dirty” or “really bad” just doesn’t convey.

“Imperative means the same thing as important, so why can’t we just say important?” asks Adele.

Because they do not mean the same thing, I tell her. I use an example from class: Booker T. Washington didn’t just think that economic opportunity was important for African Americans in the South; he thought it was imperative. A must, not just really good.

I watch Adele as the light bulb goes on; she sees the difference. And she better understands Booker T. Washington, to boot. “Wouldn’t that be a good word to use in your essay,” I ask her. She smiles.

More complex vocabulary leads to more complex thought

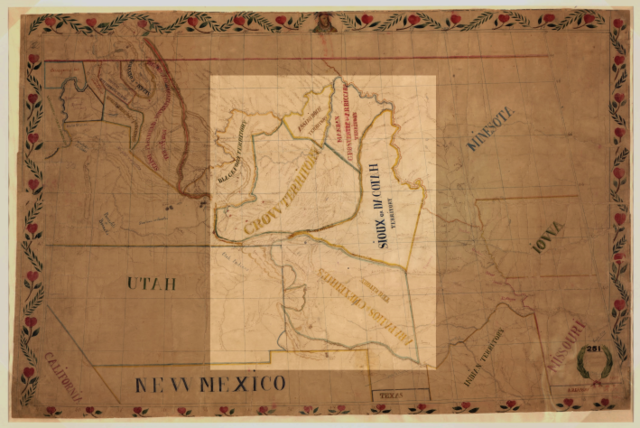

If students don’t know certain words, there are things they will not understand. For example, in a reading seminar about the westward expansion of American settlers, students were to discuss whether the author of one of the readings believed it was inevitable that the U.S. was going to break the 1851 treaty with the Lakota.

Map of Pierre-Jean De Smet in 1851. The Indian territories agreed upon in the Fort Laramie Treaty (1851) is shown in the light area.

I found myself darting around the room having to explain what the word “inevitable” meant. The question of inevitability in history is a fascinating one that middle schoolers of all levels can discuss. But it sure helps to understand what the word “inevitable” means in order to have it.

As I heard from another teacher, “vocabulary is a tool of thought.” Without a rich vocabulary, student thought is simplistic. Often, I hear students say things like, “I don’t know how to explain it.” Or they end a thought with something like, “And, uh…yeah.” Or, “you know.” “And stuff like that.”

It’s because they do not have the words.

But it’s not just fancy vocabulary words. Sometimes it’s more basic than that. Look at this example from a student’s paper about how women’s roles began to change during the Progressive Era:

Women getting involved in politics became a thing.

“Became a thing” is now “a thing.” It is an expression used in today’s speech, but this is not good writing. So we need to teach our students phrases that are used in writing, such as “became increasingly likely.”

Women were increasingly likely to become involved in politics.

The language of history

Middle school students do not know how to write like this unless they are taught. We teach them writing only in Language Arts classes. But if they are going to write in history and social studies classes, there are words and phrases they need to be able to use. (See Jeremy Hyler’s MiddleWeb post where he discusses useful words.)

In addition to words like “inevitable,” consider “pivotal” as a way to help students write about turning points. The word “iconic” or “quintessential” can help students think about cowboys and farmers as emblematic (another good word) of the American Dream.

The word “precedent” can be used to explain the significance of choices George Washington made as the first president. Was the U.S. setting a new precedent when it annexed the Philippines and Hawaii? The word “erode” can help us understand the rise of Jim Crow in the South following Reconstruction. The word “impetus” can be used to explain factors that cause other events. The Homestead Act was the impetus for westward expansion.

There are also a few words I teach my students to avoid. The words “always” and “everyone” are words ill-suited to the study of history. Rarely does a thing “always” happen to “everyone.” Suggest students use words like “often,” “in many cases,” “for many” or “for most (or some) Americans.” This will make their writing more accurate and sound more sophisticated.

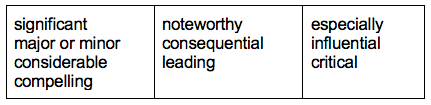

The word ‘huge’ is another one to avoid. It’s in the same category as “really bad.” Yes, the transcontinental railroad was huge. But wouldn’t it be better to describe it has having a “significant impact” on the American economy? Yes, it would. Students need alternatives to phrases like “a really big deal in history.” Here are a few:

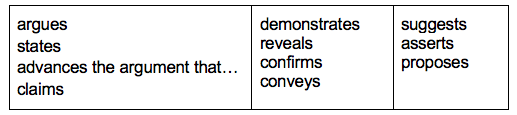

Having students use evidence from the text? Tired of “the author says”? Here are some antidotes to that:

How to teach these words and phrases so that students more regularly use them is something I am still struggling with. Maybe a phrase of the week? Word of the week? More collaboration with the L.A. teacher across the hall? Let me know what you are trying in your classroom in the comments.

Lauren, this article is so on target. I especially like your examples of when students understood why one word was better than another. In our daily current events discussions in my 8th grade history classes, I often deliberately choose headlines with difficult words, such as “denounce” or “surpass,” and we define them before we talk about the story. The WSJ and NYT tend to include such vocabulary regularly.

Your piece is inspiring me to add terms such as “precedent” and “imperative” to our beginning-of-the-year list, which usually focuses more on content-related words such as “pension” and “bipartisan.” Thank you!

My son had a teacher in 5th grade who gave the students a list of sophisticated, descriptive words. We called them, jokingly, the “more better words”. Every now and then, she would send home an essay and have them go through and replace “meh” words with more descriptive and compelling words. It was a good exercise for him, but that one class was the only time it happened. Thank you for the call to broaden this approach.

Thanks, Sarah. I love the idea of choosing headlines with challenging words. So helpful in this age when sometimes that’s all we read!

And Denise, I am going to consider having students do exercises like this. What a good idea.

This is such a great article that I will be pulling out in August as I prepare for the year ahead. What words would make the rest of the year more productive?

Thanks, Megan. I love the idea of keeping a list. I have a running google doc titled, “vocab” where I jot down words that come up in reading assignments, words that kids ask me about, words that I find in some of my stronger students’ papers, anything. I encourage you to do the same! Use my examples above as a starting point, perhaps? If any other readers have ideas, use the comments as a place to add words!

Nice Idea