5 Strategies to Teach SEL Online or In Person

A MiddleWeb Blog

Whether we’ll be teaching in-person or virtually, or some of both, it’s essential that we address our students’ social needs.

Part of our role as educators is to teach students to honor their feelings and respond to them rather than to be controlled by them or act impulsively.

This is particularly true for language learners. Over the “break” we need to consider and plan how we can best create a welcoming environment for our ELs, whether they come into our care through physical classroom doors or by joining us in virtual learning spaces.

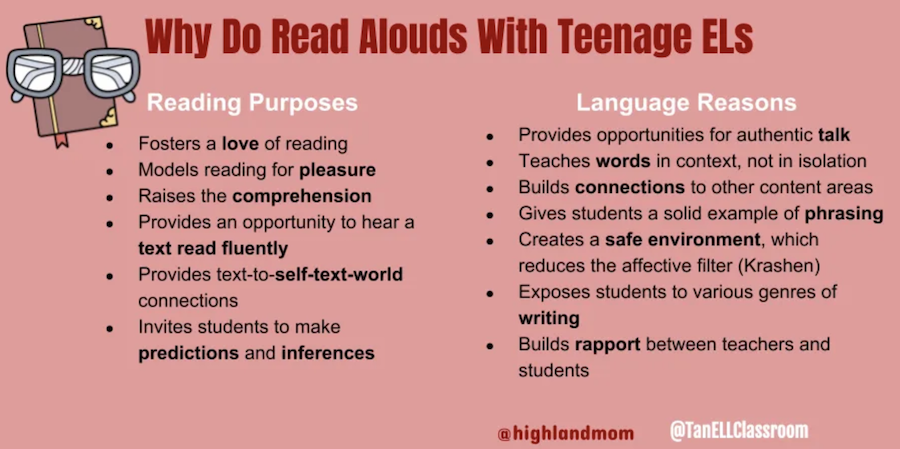

Research tells us that when language learners feel welcomed, their affective filter lowers, which creates the cognitive space for them to engage academically (Krashen & Terrell, 1983). Let’s look at how we can best achieve that goal with ELs and all our students.

5 Low-Prep SEL Strategies

A core tenet of social-emotional learning (SEL) is how we teach and what we teach are as important as how students feel. David Bott, Associate Director of the Institute of Positive Education, joined me on a podcast interview to share five low-prep, high-yield strategies to teach students skills they need to regulate their emotions and their responses.

Bott and his teammates have taken research from positive psychology, turned it into principles, and identified practical strategies for teachers to implement in a classroom context.

►Bott suggests that teachers and students are two humans in the same space first. The teacher-to-student relationship is second. Therefore, Bott encourages us to facilitate human-to-human interactions. Creating this connection means spending the first few minutes of the lesson connecting with our students.

Connecting might mean meeting students at the door and having informal conversations not necessarily related to school. For example, you could use their names in a positive way or ask how their new pet is doing, how they are enjoying their anime drawing club, how the college application is going, or how their drama performance was.

Integrating SEL will take up instruction time, but that can mean minutes, not hours. Also allow for unteaching to occur frequently. Though this can seem like a waste of time, it is a great use of our time because by connecting, we lower students’ flight, fight, or freeze responses. Establishing this rapport sets students up to focus on learning because they feel safe, heard, connected to the class and not apprehensive of the teacher.

Bott suggests that there are three components of trust: competence, honesty, and benevolence. Bott has also translated what these three components mean for a student-teacher relationship:

Competence

Students will judge our competence based on such things as how prepared we are for the class, how well we know our content, how effective we are at managing student behaviors, and how we facilitate learning experiences.

Honesty

Keeping our word to students means showing up regardless of the circumstances that we find ourselves in. Honesty can also mean providing authentic feedback that is not sugar-coated, yet not hurtful either.

Benevolence

Students need to know that we genuinely care about them – that we think about their well-being, their needs, and their wants as students. Benevolent teachers act in the best interests of their students, demonstrating that they are not showing up only for a salary.

Students do not automatically trust us. To be trusted, we must work to earn students’ belief and confidence. Remember that every interaction is either a withdrawal or a deposit in a relationship. Work to have more deposits than withdrawals.

If your class periods are longer than an hour, I encourage you to facilitate prep-free, prop-free brain breaks. In a brain break, students playfully engage with you and other students to create a sense of community and to give them a break from intensive studying. The time spent engaging in a brain break is time well invested as students who are physically active are more able to focus.

Through each story we identify the language associated with emotional intelligence, such as acknowledge, perspectives, reaction, response, compassion, empathy, and strengths, to name a few.

Throughout the year, you can bring these stories, the characters, their emotions, and their responses back when a teaching opportunity around emotional intelligence arises. As we “speak human” through the stories we tell, those stories become the tools to teach emotional intelligence skills we want all students to possess.

The more students have the language of emotions, the more they can communicate their own emotions, their own needs, their own desires. Additionally, the more vocabulary students have around language, the more they can connect, support, and empathize with each other.

The best part about this strategy is that families can get involved as well. They can recommend a story from their culture to be shared in class that can teach emotional intelligence. Teachers can also encourage families to tell stories from their culture that teach an emotional intelligence concept such as empathy, compassion, or understanding another person’s perspective.

One way I do this is by telling students stories of how I deal with challenges, obstacles, and setbacks. I might tell them about a disagreement my partner and I had and how we listened to each other, tried to understand each other’s perspectives, and shared how we maintain an affirming relationship despite the disagreement. For some reason, they seem to be attentive during these stories where they can peer into my life. With my school-appropriate real-life stories, I show students how I am human. I make mistakes, and I’ve learned from them.

Lastly, as language specialists, we get the distinct privilege of being human through our co-teaching. We can show them explicitly how we take turns, rely on each other’s strengths, support each other, process our disagreements in a healthy way. We not only get to co-teach on behalf of language learners, we get to use co-teaching to give life to the emotional intelligence skills we want students to learn. Sometimes, if we want students to learn something, we can practice it ourselves first.

Using SEL Strategies Online

If your students have access to technology, you can transfer these strategies online. For example, you might welcome students to your virtual meeting by asking them to rate how they are feeling today before going into the content part of the lesson. You can also allow students to turn on filters that can transform a face into a fruit, a cowboy, or an animal. You can even turn on the filter on your side and turn your face into that of a unicorn.

Here’s another example: you can garner trust when they notice that you already prepared a welcome video for them to watch with their partners in their breakout groups. They can tell you have already thought about all of these details, and they trust you enough to go along with the lesson.

In the welcome video, you could explain that you found a better way to do virtual school because you listened to a podcast where the host has an expert on flipped instruction speak about using more synchronous collaboration during virtual schooling. You now have an opening to emphasize that you made a conscious choice to make things better even though you have never facilitated breakout groups virtually before.

This example demonstrates how you can layer in all the strategies that Bott suggests into your virtual instruction. There is no need to do something separate. You can simply find opportunities to teach emotional intelligence that are already inherent in your virtual instruction.

SEL Begins with Our Teaching Mindset

If I want to reach into the future, I must first touch the present. I have to intentionally integrate students’ need to develop emotional intelligence into the curriculum so they become adults who can more wisely regulate their emotions.

That’s what I appreciate so much about Bott’s suggestions. Social-emotional learning is not a program we add on; it’s a mindset we teach with. I have to teach content with an eye for opportunities to develop students’ emotional intelligence. I not only teach students to understand why Romeo was so upset with his family but also teach them to consider how ineffective he was in dealing with his feelings and what that led to.

I cannot delegate or simply hope that students will develop highly-effective social-emotional skills. I have to commit to integrate this skill-building into my lesson, model it as I work with colleagues, and embody it with each interaction I have with students. After all, emotional intelligence is what they will need in the future long after they have forgotten how to find the area of a right triangle.

Krashen, S.D. & Terrell, T.D. (1983). The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. Prentice Hall Europe.

This article was of great interest to me! Thank you so much!