The U.S. Constitution Meets the 7th Grade

A MiddleWeb Blog

So now that I have returned to the classroom as a 7th grade U.S. history teacher, how did my Constitution Unit fare? Was I right? Can I go beyond “the Executive branch enforces the laws; the Legislative branch makes the laws; and the Judicial branch interprets the laws” memorization approach?

And what else have I learned about teaching history to middle schoolers based on my recent return to full-time teaching?

I hope you smile with empathy when I report mixed success. Here’s a bit of what I have learned specifically about teaching the Constitution this year.

You need to teach the basics first.

Enthusiastically, I jumped right in with little basic introduction to the document. Whoops! I should have known better. While some seventh graders already knew that we have three branches of government and what they are, many did not. An overview was in order before delving in, allowing a full period to look at the document, note its parts, examine a diagram that illustrates the three branches.

All of this would have been worth additional time. But I had spent more time than I had thought I would on the Revolution, so I was too eager to get going. Next time I will remember: slow and steady wins the race when the Constitution is in the room.

Once the basics are covered, you can teach the Constitution at a high level.

You can even have 7th graders reading the actual Constitution and analyzing challenging questions. I had my students read for themselves the places that describe what Congress does and what Congress cannot do and then answer questions based on the reading.

While we had a workbook, I insisted on supplementing it with their own copy of the Constitution that they could annotate. I gave them historic examples of what has happened in the past and had them apply Constitutional principles to answer questions, such as the case of Nixon refusing a House subpoena to hand over White House recordings. I told them in advance that this was a really hard question that I had trouble with when I was in graduate school.

Middle school teachers won’t be surprised to hear that they LOVED that approach – the approximately three-quarters of students who got the question right were thrilled that they were “smarter” than their teacher, and the ones who got it wrong couldn’t feel bad because I told them I had gotten it wrong the first time I looked at it, too.

Students who found answers to questions in the Constitution itself had a lot of pride on being able to read the august and somewhat intimidating document for themselves.

Connecting the Constitution to current events is essential.

Sometimes it felt like a presidential election year with so much national politics in the news on a daily basis. Next year, of course, we will all have to spend time on the election. But even this year, it was great to take class time to discuss what was going on.

We talked about what could happen if Trump decided to run as a third party candidate and how that could affect the outcome in the Electoral College. We discussed the President’s role as Chief of State and Commander-in-Chief as it applied to the recent tragic events in Paris and the ongoing war in Syria. We discussed the role of Congress as it applied to immigration with regard to the Syrian refugee crisis.

Students also had to work on an outside class project where they found news articles pertaining to issues of their choice and then found linkages between those articles and aspects of the U.S. Constitution.

Speaking of that current events project . . .

Again, I have learned the hard way that sending tween-aged students off to the internet to “find articles” is too vague. While most understood what I meant by “current events,” at least some students found “articles” on such places as the White House’s website or the House of Representatives which were high quality, but not “current events.” So I took some class time to demonstrate how to search for news articles on topics that interested them. Next year, I will do this at the beginning.

And what is “current” to a 12-year old?

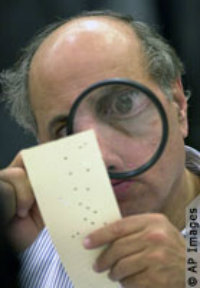

Hanging chad hunt, US 2000 election

Things that to me are still “recent memory” are ancient history to seventh graders. None of them was even born during that most bizarre election year of 2000. So while the Chad Affair is a great example of how the Electoral College can turn out some strange results, it is not a current event.

Nor is Bill Clinton’s impeachment proceeding. I knew that would have to be explained carefully to students. But I was surprised to realize that some students didn’t know that Hillary Clinton was the wife of a former president. It is important to remember that things we take for granted as teachers as common knowledge are not to our young students.

Work days are a great idea.

Years ago, when I taught high school, I gave homework. I would never “waste” a class period on just letting students do their homework in class. My philosophy on this has changed quite a bit, now that I am also a parent. (I have posted on this here and here). And teaching middle school is NOT the same as teaching high school. I have purposely designed my class to minimize the amount of work students must do at home.

But I do give some home assignments.

One day a few weeks ago I was feeling overwhelmed. I was behind on grading, lesson planning, and most important, sleep. My students seemed to be in a similar boat. When I started getting emails from some of my strongest students who were worried about their current events project, I knew it was time to rethink things.

So I let them work on one of the Constitution readings with questions in class instead of simply assigning it for homework. And if they preferred, they could work on their current events project, or do that when they were done with the short reading/question assignment. They did this for the whole period. Quietly at their desks. If they needed help, I said, ask me.

My students got a ton of work done. I spent the period going from student to student, answering questions, giving encouragement, prodding them to do a little more. Again, I learned that sometimes everyone learns more when I slow it down and give them time to catch their breath.

Going off on tangents isn’t always bad. . .

I spent the better part of one class period answering really random questions students had about the Presidency. Things like what happens on Inauguration Day? Why is the Vice-President sworn in first? Does the President have to be sworn in on a Bible? What happens if the president is assassinated? Do the Secret Service really follow the President everywhere? Even the bathroom? Do they go to school with his kids?

7th graders really want to know these things. At any given moment, at least six or seven students had their hands up. I could have spent another 40 minutes answering their questions. This was one of the most engaging lessons I taught. Even students who have zero interest in history, government or current affairs have heard of the President of the United States. They have seen Obama’s face everywhere.

Pausing to answer questions that kids find interesting was worth the time. I didn’t finish everything I had planned to that day, but when the bell rings and they are sorry, you know you are doing something right.

So what didn’t I get to?

A million things. But this will not be the last time they will study the Constitution this school year.

In the next few weeks we will look at the debates between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson over the National Bank and then the Louisiana Purchase and see how each person used the Constitution to justify his views. We will learn how the party that is in power will tend to use the elastic clause to expand government, while the party that is out of power will tend to argue the opposite. And we will see how similar arguments play out today.

We didn’t get to the significance of the Fourteenth Amendment, but I will build that into our unit on Reconstruction.

We will have a few “First Amendment Fridays” to debate and discuss some things we didn’t get to before the test. Realizing I was running out of time, I purposely “cut” religion out, figuring it might be a fun and timely thing to discuss on the Fridays leading up to Hanukkah, Christmas and the winter break.

I can hardly wait until Friday. . . .

________

Image credit: Syrian refugees by Mstyslav Chernov

Our 6th grade classes just finished our unit on the creation of the government, including a debate between the Federalists and Antifederalists. To get the Constitution adopted, there had to be a compromise, hence the Bill of Rights. I then incorporated that as a separate lesson, reviewing the amendments and then assigned the classes to find the rights and responsibilities of parties included in three fictional case samples. The kids loved the give and take and the ability to apply the amendments to real life situations. Just another way of bringing government into the forefront.

I love it! I have found that kids really respond to learning about actual cases involving the Bill of Rights. Last week, on the 2nd of my “First Amendment Fridays” we looked at an actual case of a Sikh student being barred from school for carrying a ceremonial knife, known as a kirpan. Read the original article here: http://articles.latimes.com/1994-04-16/news/mn-46529_1_school-district. Students were surprised to hear that the Court of Appeals ruled on the side of the student! Eager to hear from others about what cases have worked well in class.