Help Students Get Smart about Those ‘Smart Pills’

Back in the real world, are there over-the-counter drugs available that could actually increase our brain function significantly? Apparently, many people think so.

Reports of the use of so-called “brain boosting” supplements or “nootropics” on college and high school campuses crop up from time to time. Not everyone is convinced of their effectiveness. A September 2019 article in the Men’s Health Watch newsletter published by Harvard Medical School warned “Don’t Buy into Brain Health Supplements.”

As the article relates, dietary changes might eventually be found that help magnify our brain power, but there’s no solid research yet to support the current over-the-counter supplement formulations, some of which can cost up to $100 a month. In fact, as one researcher told the HuffPost, the only truly proven mental stimulant as of 2019 is our old friend caffeine.

What do students hear?

For the past several months, I’ve heard a commercial for a “miracle” pill for the brain called – no surprise – “Limitless.” The one-minute spots (long ads for radio) are frequently aired on national newscasts at the top of the hour. In fact, that’s when I heard it, while driving in my car.

I wondered: do students, listening to voice-only commercials, ever question what they hear? If they do, great. But what if they don’t? Are they susceptible to being fooled? Could they be persuaded to purchase a product based solely on the claims made in these types of ads?

In this post I call attention to some of the techniques used in on-air ads and suggest some ways you can encourage your students to think twice.

Limitless claims

Listening skills become increasingly important when students encounter audio-only ads they hear over the radio, in online media, and via satellite services. Good listeners can apply their skills to break down the techniques of persuasion.

For example, can students name the product being advertised (and suggest reasons why the name was chosen)? Can they recognize the gender of the person(s) pitching the product? Why were these particular voice actors chosen?

Can students recall any words, phrases or slogans the advertisement used or repeated? Can they recognize other engagement techniques (like music, sound effects, etc.) that might have been incorporated into the ad for psychological effect? Does hearing the ad over and over make it stick?

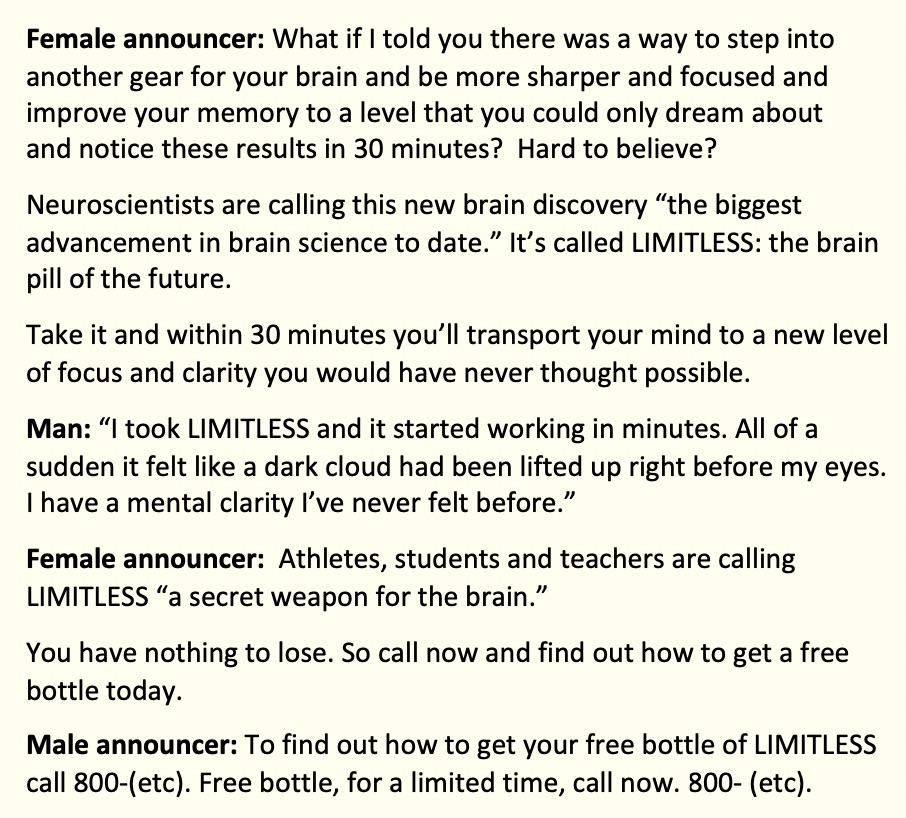

I wrote down what I heard in the Limitless radio ad:

One of the first things that caught my attention was the claim that neuroscientists call it “the biggest advancement in brain science to date.” I suggest you have your students research that phrase and see what they come up with. When I googled it, I found several websites use that quote to describe other products claiming to improve brain function. The names of the neuroscientists are never provided, even though other so-called experts might be quoted.

The spot also claims that athletes, teachers and students say it is “a secret weapon for the brain.” Googling that phrase came up empty. You might ask students what comes to mind when they hear the phrase “secret weapon.” “Something surprisingly powerful and super-effective” might be a typical response.

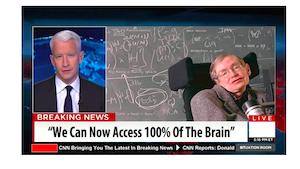

The use of well-known names is one of the more popular “propaganda techniques” known as “testimonial.” Testimonials from well-known persons are meant to persuade and convince the consumer that if __________ says it works, then it must be good enough for me.

Lesson idea: Testimonials are powerful and they often work. You might ask your students to locate and share a product that is currently being promoted by a singer, celebrity or sports figure. It should not be hard for them to do. But what if the celebrity testimonials are fake? This story at the Quartz website would be a great teaching tool.

Another kind of testimonial is heard in the Limitless radio commercial, but this one is not attributed. It’s a man’s voice who says “I took LIMITLESS and it started working in minutes. All of a sudden it felt like a dark cloud had been lifted up right before my eyes. I have a mental clarity I’ve never felt before.”

Inserting this kind of fake “customer,” who testifies about the success of the pill, is known as the “everyman” or “plain folks” propaganda technique. People listening may assume that this is a real user of the product and that if it worked for him, then it might work for me too. (Ask your students to locate a print, broadcast or online ad for a product that is currently being promoted by someone who looks or sounds like them.)

Researching questionable supplements

Using the well-known SNOPES “fact checking” website, I found that a similar brain boosting product was judged unreliable. “We could find no proof that the supposed brain supplement InteliGEN enhances brain function or is even safe to use.” (Source) A quick web search for a term like “brain enhancer” will turn up dozens more supplements with similar ingredients.

The Federal Trade Commission is another reliable source for students to conduct research. In April of this year, the FTC settled with twelve corporate defendants because they had deceptively marketed “cognitive improvement” supplements using sham news websites containing false and unsubstantiated efficacy claims, references to non-existent clinical studies, and fraudulent consumer and celebrity endorsements. (Source)

Students might be interested in learning more about the current debate over the regulation of health and dietary supplements in the United States. One good source is the public interest group Public Citizen which lobbies for greater regulation of the supplements market.

With few exceptions, there is no evidence that dietary supplements are safe and effective for their marketed uses. Because supplements are regulated as foods, they are exempt from the tougher regulation accorded to drugs. But like drugs, supplements should be shown to be safe and effective for their purported uses before being marketed.” (Public Citizen)

The FTC explains current dietary supplement regulations here. Students might also explore the Vitamins and Supplements section of the Consumer Reports website for insights about supplements and deceptive marketing. One article that’s particularly helpful: What supplement labels mean – and don’t.

I located two products on the popular shopping site Amazon that used the name LIMITLESS. One of them says “As Heard on the Radio.” You might challenge your students to deconstruct the online claims as well. Above is the Amazon link to the LIMITLESS product with the radio connection. Here is a link to its well-designed website, which could easily serve as a case study in potentially misleading marketing techniques.

Questions for students to consider:

1. Are the actual ingredients contained in these products listed? If so, what do they know about how these ingredients work, if they do at all?

2. How much do the products cost? How might that compare to popular vitamin supplements with similar ingredients? Why would a “free bottle” be offered if the product isn’t effective?

3. Did the students consider the “legal disclaimer” about whether the product had been evaluated by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration)? Did they hear/find a statement saying something like “*Individual Results May Vary”? What purpose might that serve?

4. Did your students read/consider the comments from people who claimed to have used the product? How might these be verified? (On its website the Limitless product claims over 6000 reviews with 4.5 stars. Where are the reviews?)

5. What is the procedure for reporting a deceptive or misleading ad to local, state or federal authorities? (Resource)

Media literacy begins with critical thinking

I chose to look at radio ads in this post, but we know that advertisers and marketers employ many different media formats to reach their audiences, and they often use persuasive (and sometimes deceptive) techniques to sell their products and services.

In a world where we want our students to become better critical thinkers, viewers and listeners, it’s important that they be exposed to a variety of marketing formats as we consider the techniques marketers use to convince consumers.

Media literacy is becoming more important than ever, I think you’ll agree. I’d love to receive your feedback on the topic discussed here. You can comment below or reach me via email: fbaker1346@gmail.com or via twitter @fbaker.

Sources and resources

► Guardian: “Students Turn To ‘Smart Drugs’ To Boost Grades”

► Snopes Weighs In on Brain Boosting Pills

► FTC Ruling Cites Brain Pill Producers

► HuffPost: “Do Brain Boosting Supplements Actually Work?”

► TIME: Nootropics, or ‘Smart Drugs,’ Are Gaining Popularity. But Should You Take Them?

► Teaching tool: a Brain Organix webpage promoting the supplement as an Adderall substitute (includes altered video and fake social media).

Thanks