Meeting Objections in Your School Community

By Ron Williamson and Barbara Blackburn

Ron Williamson

Every school leader has faced resistance to their plans. Occasionally even the most routine activity or slight alteration in schedule or program will engender resistance.

While resistance is often easily overcome, it sometimes takes on more overt forms. A person may go beyond basic objections in an effort to derail your plans.

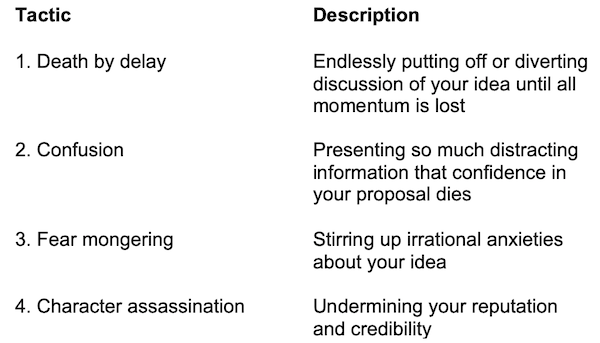

Objections can manifest themselves in four ways:

Most leaders recognize these forms of resistance, particularly the first two. If you’ve ever experienced any of these strategies, you know it is difficult to move past them. Often the person(s) using these tactics influences others, and the resistance can grow into a larger problem.

Barbara Blackburn

Barbara was working with a local school. As she arrived one day, the principal met her at the door to share a problem which had arisen. Due to recent declines in test scores, changes in the assignment of teacher assistants were required. The shift would move assistants from several classrooms and place them with teachers in content areas of greatest need.

He had data to support the plan, but instead of building consensus, he had asked the teachers to vote on the plan. The teachers losing assistants voted no, and they comprised the majority of the staff. As he noted, “Now I have to go in and tell them their vote doesn’t count. We’re making the change anyway.”

When he shared the decision with teachers, some of the faculty immediately used some of the tactics listed above. Several shared “worst-case scenarios” of what would happen to their students if the plan went through (fear mongering), and one teacher began to accuse the principal of incompetence and a personal vendetta (character assassination).

Even though the idea of sharing assistants across content areas had merit, it never happened because of the objections of teachers. The principal decided to withdraw the plan and begin anew.

Solutions to Objections

How do leaders respond to uncompromising resistance? Here are some strategies you might use to diffuse each type of objection so that you can move forward with positive change.

Death by Delay

With death by delay, a teacher, parent, or other stakeholder tries to slow down discussion and action on an issue, hoping that by holding up the conversation, people will lose interest and move on to something else. Sometimes a person asks for straw polls or for a task force to study the idea further.

This usually occurs after you have already gathered input through conversations, surveys, and focus and leadership groups (an important first step). But by asking for additional input, they stall action. A common response is “We need to study this more” or “We have too much on our plates right now – can we look at it next year?”

In order to respond to delays, be sure to use a variety of strategies to gain input and garner support for your plans. Provide a reasonable amount of time for discussion and reflection, but set a deadline and stick to it. Also, be prepared with succinct, fact-based responses to questions and comments. Referring back to earlier discussions or surveys is helpful.

Confusion

Confusion is another tactic to resist change. In this case a person tries to derail your ideas with questions about irrelevant facts. You also might end up in a conversation that is so convoluted you cannot sustain a meaningful dialogue about the subject. Statistics are often used to confuse the issue. Although data is important, someone who is trying to confuse the issue will focus in on an outlier or find outside data that does not support your plan.

The most appropriate response to confusion is clarity. Provide clear explanations on your strategy as well as a well-defined rationale. Keep it short and simple, and when a person continues to be confusing, return to your focus on your well-supported facts.

A few years ago Ron helped a Chicago area district develop plans to strengthen their middle school program. Some teachers in specialty areas resisted changes and often used phrases like “in my experience” to challenge data. The work group established norms that required speakers to cite data or provide research that supported their positions. They chose not to use “experience” as supporting data. Adoption of that norm changed the discussion.

Fear Mongering

With fear mongering, a person attempts to raise anxiety and prevent a thorough examination of a proposal. People begin to worry that implementing even a good plan can be filled with frightening results. We worked in a school that was considering implementing 1:1 technology. In the teachers’ workroom there was an animated conversation about all the dangers of the plan.

Fear-inducing statements included “What if students break them?” “If we buy the technology, we won’t have money for other supplies!” The entire conversation was fear based, in fact.

In this case, the principal shared information that assuaged their fears, and the implementation was successful. Once again, sharing clear information about the realistic outcomes of your plan is critical.

Character Assassination

Typical comments include “She’s a first year principal; she doesn’t really understand,” “I heard about him from his previous school. He’s always trying to control things” and “She’s just doing this to impress the district.”

This type of objection is particularly challenging, especially because it is so personal. There is no focus on the issue – only on you (or other decision makers you work with). There are two main strategies when you face this:

- Stay above the personal negativity. Do not respond in kind.

- Focus on the facts and involve other respected stakeholders to help balance the negativity.

Final Thoughts

Dealing with resistance and objections to change is always a challenge. Leaders who are most successful overcoming resistance are those who are very inclusive during the planning stage, widely share information with everyone involved on the front end of an initiation, and have a well-thought-out implementation plan.

NOTE: Some of the ideas in this article are drawn from the work of the late Dr. Robert R. Blackburn, co-author with Ron and Barbara of Advocacy A-Z (Routledge/EOE, 2018).

Feature image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, a “Top 30 Global Guru in Education,” is a bestselling author of over 30 books and a sought-after consultant. She was an award-winning professor at Winthrop University and has taught students of all ages. In addition to speaking at conferences worldwide, she regularly presents virtual and on-site workshops for teachers and administrators. Barbara is the author of Rigor in the Remote Learning Classroom: Instructional Tips and Strategies from Routledge/Eye On Education.