The Pathways to Literacy Are Entwined Around Us

By Jason D. DeHart

Simply put, when I think of the term literacy, I think of navigation. This post will explore observed literacy practices from an educator who has been working in the classroom for a little over 15 years.

I want to make the case that literacy is not an elusive set of complex practices in pursuit of amorphous standards – far beyond the reach of some students – but instead a state of learning and being that can be achieved using a wide range of readily available media modalities.

Indeed, reading, writing, composing, scripting, producing, viewing, and more are all skill sets that are readily accessible by “kids these days,” a truth that in some ways can be a reassurance for those of us trying to get students connected to literacy each day.

“I Am Iron Man.”

While Batman was the popular character in media for me as a young reader, Robert Downey, Jr’s portrayal of Iron entered the fray for students in my first year of teaching. When I began my career in middle school, one quick take-away that I found by the end of that first year was that perspectives on popular stories had changed.

Space Jam and Independence Day were big news when I was a middle school student, but comics and their heroic characters were already becoming a central part of media. Marvel was already present in film through characters like the X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002), but the Marvel Cinematic Universe was just budding.

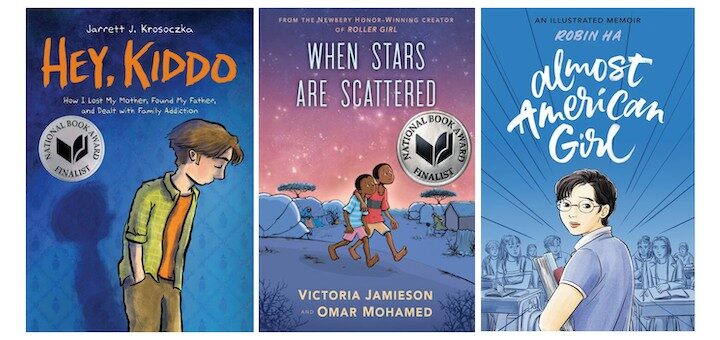

Story upon story from the pulp comics became part of popular media, with interlocking tales, and links not only to the movies but television and YA books. While my adult self sometimes felt a little embarrassed to visit the magazine spinner racks of my youth, operating on the unspoken assumption that reading comics was a sign of arrested development in older readers, my students embraced comics narratives.

I recall seeing a middle school student who I knew to be a reluctant reader actively engaged with the novelization of the first Iron Man film, completing the journey from comic to movie to a softbound text of 250+ pages.

It was not long before I observed the occasional “graphic novel” appear in the school’s book fair, and by the end of my second year of teaching, my students were making comics with me (and on their own) as part of literacy practice.

Text to Text

For middle school students living and learning now, texts and ideas are arranged in quick succession. TikTok thrives on rapid feeds, and students have access to virtually any narrative with a few clicks on their cell phones. When my class has a puzzling question about a story or needs to investigate a topic, a plethora of resources are available. The trick is to approach these many texts critically through steps, sets of questions, and intentional noticing about authorship and messaging.

Texts are no longer isolated realities, with one segment of a story trickling in every year at a print publisher’s whim. Young adult fantasy, science fiction, horror and “literary” series are now often published in rapid succession. Video games become books; books become video games. Through these interlinked franchises students who discover engagement with one type of media can quickly encounter what Henry Jenkins called convergence culture as successful titles are reworked across various types of storytelling formats.

When it comes to critical reading, this also means that opportunities for comparisons are ripe, and questions for authors (including directors and video game developers) are ready to be posed. While I do want my students to engage with the printed word and discover new and vibrant vocabulary that can shape their thoughts and feelings, I also recognize that most if not all of the English/Language Arts standards can be addressed (and experienced) across multiple forms of media.

Need to know what theme is? Find a message in media. Need to explore character development? Observe three clips from The Batman and tell me what we learn about Bruce Wayne at each turn.

Reaching Our Striving Readers

While I understand that our students are immersed in textual worlds and need text-related skills, I would also argue that having access to media and experiencing the kind of classroom instruction that values multiple modes of pursuing meaning can be encouraging for students who might be termed “readers who are striving.”

Sometimes, for a variety of reasons, students are simply not comfortable engaging with a full page of typeset prose. At other times, a student may lack the experience, confidence or necessary skills to feel comfortable composing a full-form essay for us. By opening up access to multimodal creation, including the tools that can be found in digital spaces, the learning conversation can begin.

I am not suggesting that skill development stops at the creation of a media construct or visual composition, but that a student can begin to practice communication this way. The stories and authorial choices that can be celebrated in chapter books can be previewed and acknowledged in a range of media products related to those chapter books – all progressing our students’ literacy development.

Conclusion: Literacy as a Transforming Practice

I want all of my students to know that I see them as readers. Some kinds of literacy still evade me. Reading quantitative research reports, for example, is still a daunting task. Making it through an absurdist tome filled with playful language still requires me to read and reread.

Ultimately, I want my students to celebrate Story with a capital “S” – I want them to make heart and mind connections so strong and that they love so much they have to continue writing and drawing about it in multiple notebooks (as I once did as a young student). If the way to lead kids to that celebration is through multiple modes of storytelling, does it still count as literacy? Of course it does.

Dr. Jason D. DeHart teaches English at Wilkes Central High School in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. Earlier he taught middle graders English in Cleveland, Tennessee for eight years and then served an assistant professor of reading education at Appalachian State University before returning to his first love, the secondary classroom.

Jason’s work has appeared in Edutopia, SIGNAL Journal, English Journal, The Social Studies, and the NCTE Blog. See all of Jason’s MiddleWeb posts here – including a 3-part series with teacher and school librarian Jennifer Sniadecki on using picture books with middle level readers. His website, Book Love: Dr. J. Reads, offers book reviews and author interviews.