Civil Rights: How Pictures Changed America

Chances are you or your students have never heard of Charles Moore. Moore was a photographer whose assignments made him a witness to many historical moments during the Civil Rights Movement.

You’ve no doubt seen the photojournalism of this small-town Alabama native, who began his career working for the Montgomery newspapers. During the 1960s, his powerful images were published in many US newspapers as well as in LIFE magazine, the news and popular culture weekly, which devoted dozens of pages to his work.

Charles Moore, with gas mask, after a long night of violence during the University of Mississippi riots in 1962.

If your students think a photo can’t change history, have them think again. If they thumb through histories of that time period, they’ll come across iconic still photographs that shocked the nation and influenced the decisions of important leaders. Moore believed that his photos would cause people to take political action. He was correct. And he wasn’t alone.

News photographers, as well as TV news crews, were regularly witnesses to the protests and police violence associated with the activities of the movement’s leader, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr, capturing his famous oratory and documenting frequent confrontations with white authorities in the segregated South.

It was those images, appearing on the front pages of many newspapers and on the nightly news broadcasts, which helped bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964, according to US Senator Jacob Javitz (source), and set the stage for passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

King was well aware of the power of the image to communicate – perhaps more effectively than any written or spoken word. Events were scheduled by civil rights leaders to take advantage of TV news cameras and broadcast deadlines.

Andrew Young, a key advisor to King, understood the importance of television and photojournalism: “In the Civil Rights Movement, it was our ability to package a message to illustrate our cause in a 60 second segment on the evening news that was key to our success. We could not have been effective without television.” (Source)

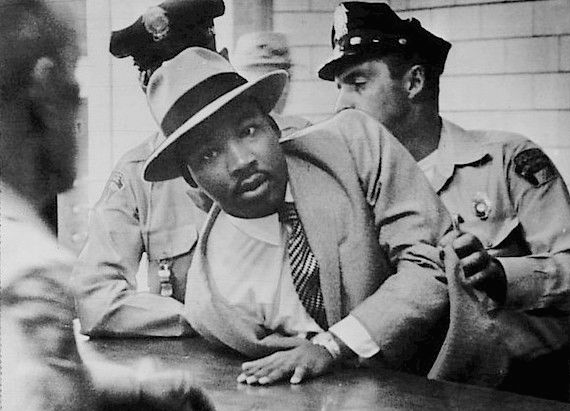

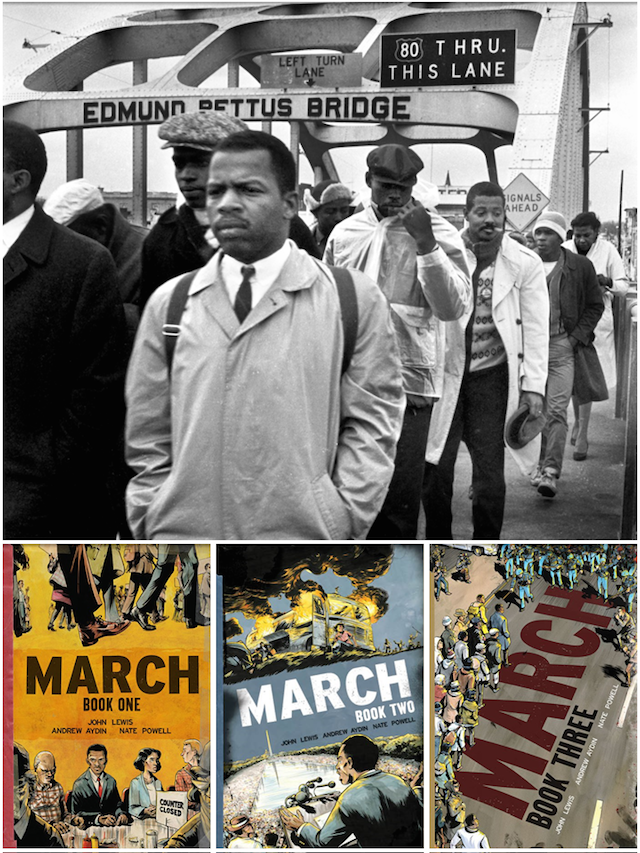

John Lewis and the Selma march

Another civil rights activist, now-U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D-GA), was a young man when he was injured in March of 1965 by Southern law enforcement officers. Lewis led the Bloody Sunday march in Selma, where Alabama state troopers attacked peaceful protesters with billy clubs, bullwhips and tear gas. The photo below shows Lewis on the ground trying to ward off a blow. It was taken by another Alabama-based photographer, Spider Martin, whose time as a Birmingham News staffer parallels Moore’s experience. (See this New York Times story to access more of Martin’s images.)

The horrific actions in Selma were broadcast on nightly news reports into living rooms across America. (Source) Selma’s mayor was stunned, admitting “I didn’t understand how big it was until I saw it on television… That looked like a war; that went all over the country.” (Source)

For more iconic Civil Rights images associated with Lewis, see the recent PBS documentary John Lewis – Get in the Way.

Moore at the heart of the action

In the summer of 1963, Charles Moore was already a veteran of the civil rights movement. Moore was present in Birmingham, Alabama when dogs were used by local police to quell peaceful anti-segregation demonstrators. This powerful image, of a dog tearing the pants off one man, made its way into LIFE magazine, which at the time it was read by half of all Americans.

TIME magazine has recognized this photograph as one of the 100 Most Influential Images of All Time. Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., referencing the then-Commissioner of Public Safety for the city of Birmingham, said of the image: “The photographs of Bull Connor’s police dogs lunging at the marchers in Birmingham did as much as anything to transform the national mood.”

Moore, who died in 2010 at age 79, believed his camera was his tool, something more powerful than any gun or knife, because his photographs captured the tension and emotion of everything in the photo’s frame. “I Fight With My Camera” is a short and compelling documentary about the civil rights movement, featuring Moore’s images and his own voice, talking about many of his pictures and expressing his feelings during that time period. (Teachers might find portions of this 2005 video effective with more mature students. Preview it first.)

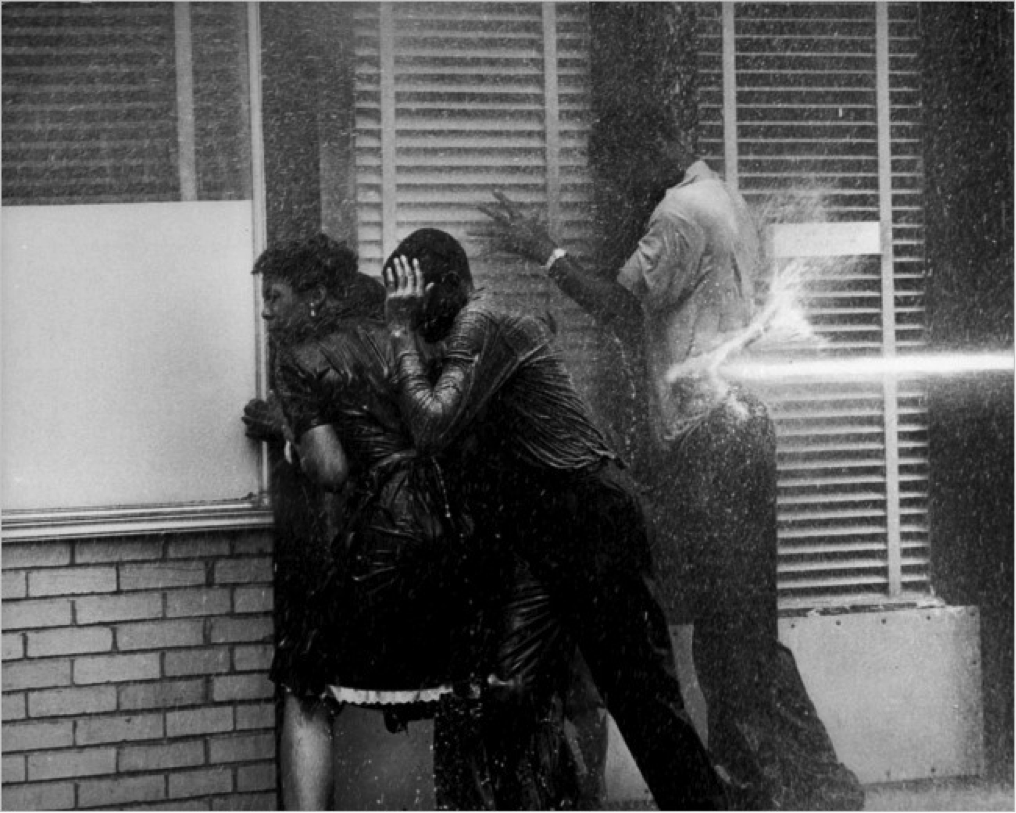

Another of Moore’s famous images showed marchers being blasted at close range by powerful fire hoses as they huddled in a doorway, futilely seeking shelter from police in Birmingham. (Source)

In their Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Race Beat, noted journalists Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff describe how Moore used a short range lens, forcing himself to get very close to the action as he documented the aftermath of the fire hose moments. Moore got so close to a stoic-faced man whose hat and shirt were soaking wet that he said he could see drops of water, like tears, coming from the man’s eyelids.

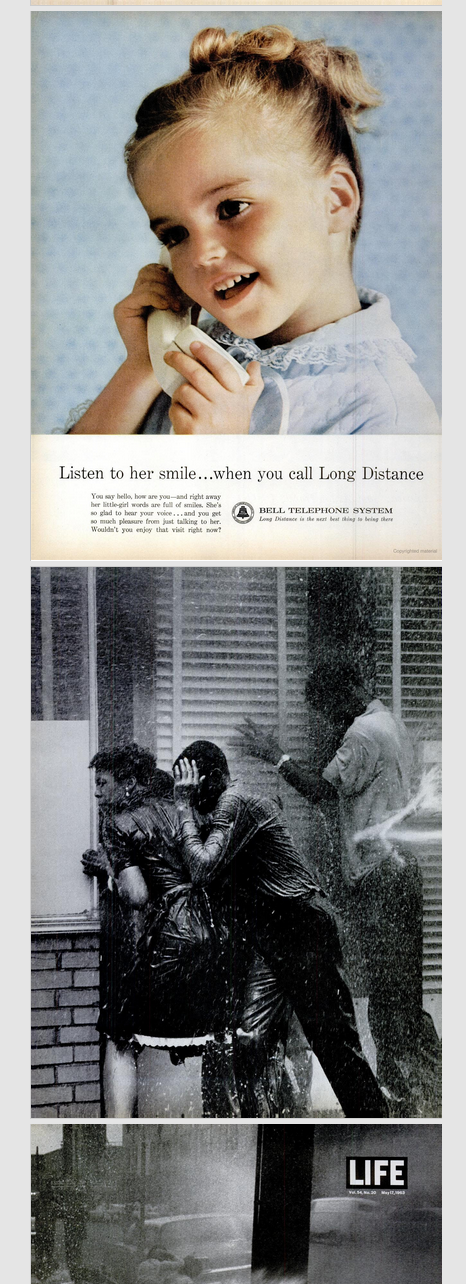

This sequence of pages from LIFE (5/17/63) contrasts homey era advertising and the harsh realities of civil strife in America.

At Google Books, you can view the complete May 17, 1963 issue of LIFE and see how Moore’s firehose images and other photos from Birmingham were presented to America in the most popular magazine of the time. The photo spread begins on page 26 and carries the headline: “The Spectacle of Racial Turbulence in Birmingham: They Fight a Fire That Won’t Go Out.” And “Provocation and Reprisal Widen the Bitter Gulf.” As many commentators have noted since, the impact of page after page of these images is difficult to overestimate.

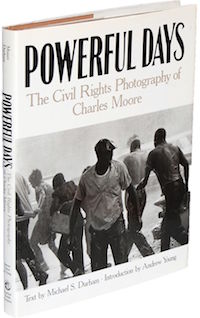

These and other Moore photographs appear in his 1991 book Powerful Days, a title I believe should be on the shelf of every school library. Many of these images, and similar ones, show up in American History textbooks and in documentaries teachers might use in February during Black History Month (see my recommended resources at the end of this post).

Using these images with students

We might ask students: How can a single photo influence the viewer? Looking at examples from the work of Charles Moore and other civil rights era photographers, what elements in the images make them stand out from ordinary photographs that might appear in newspapers and magazines? What impact might such images have had on Washington lawmakers and other influential Americans who were witnessing the events in the southern United States from afar? Do the images tell a story without using words? Images like these often provoke emotion – are they “fair reporting”?

Having your students study and analyze such images can be part of important visual literacy lessons. Understanding the context of the images and the events surrounding them is also important in today’s political climate, when lessons of the past are not always recalled with clarity.

Recommended Resources

► My web page: “Images of the Civil Rights Movement.”

► My MiddleWeb article on Black photographer Gordon Parks including several segregation-era photographs.

► The Civil Rights Movement from Behind The Lens (Interview with Charles Moore at Southern Scribe)

► Documentary Photography: Civil Rights Through Image and Text (Lesson plan – Getty Museum)

► The Role of TV in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement (online essay)

► The Role of News Media in the Civil Rights Movement: Selma March (PBS)

► Photographing the Civil Rights Movement (Julian Bond & Civil Rights photographer Danny Lyon – National Geographic)

► Eyes on the Prize: Then & Now (Award-winning PBS documentary series plus a 2016 update – World Channel)

► A Selection of Civil Rights Photography from U.S. News (Library of Congress)

► Captioning the Civil Rights Movement (ReadWriteThink lesson plan)

► For a look at other iconic images that “have changed the world” see this CNN report.

________________

Frank’s new book Close Reading the Media: Literacy Lessons and Activities for Every Month of the School Year can help teach middle school students to become savvy consumers of the TV, print, and online media bombarding them every day. The book is copublished by Routledge and MiddleWeb. Use discount code MWEB1 for 20% off the cover price.